In the United States, there is no official accounting of the people

killed by police. To address that void in information, non-governmental

and news organizations have been collecting data on such incidents.

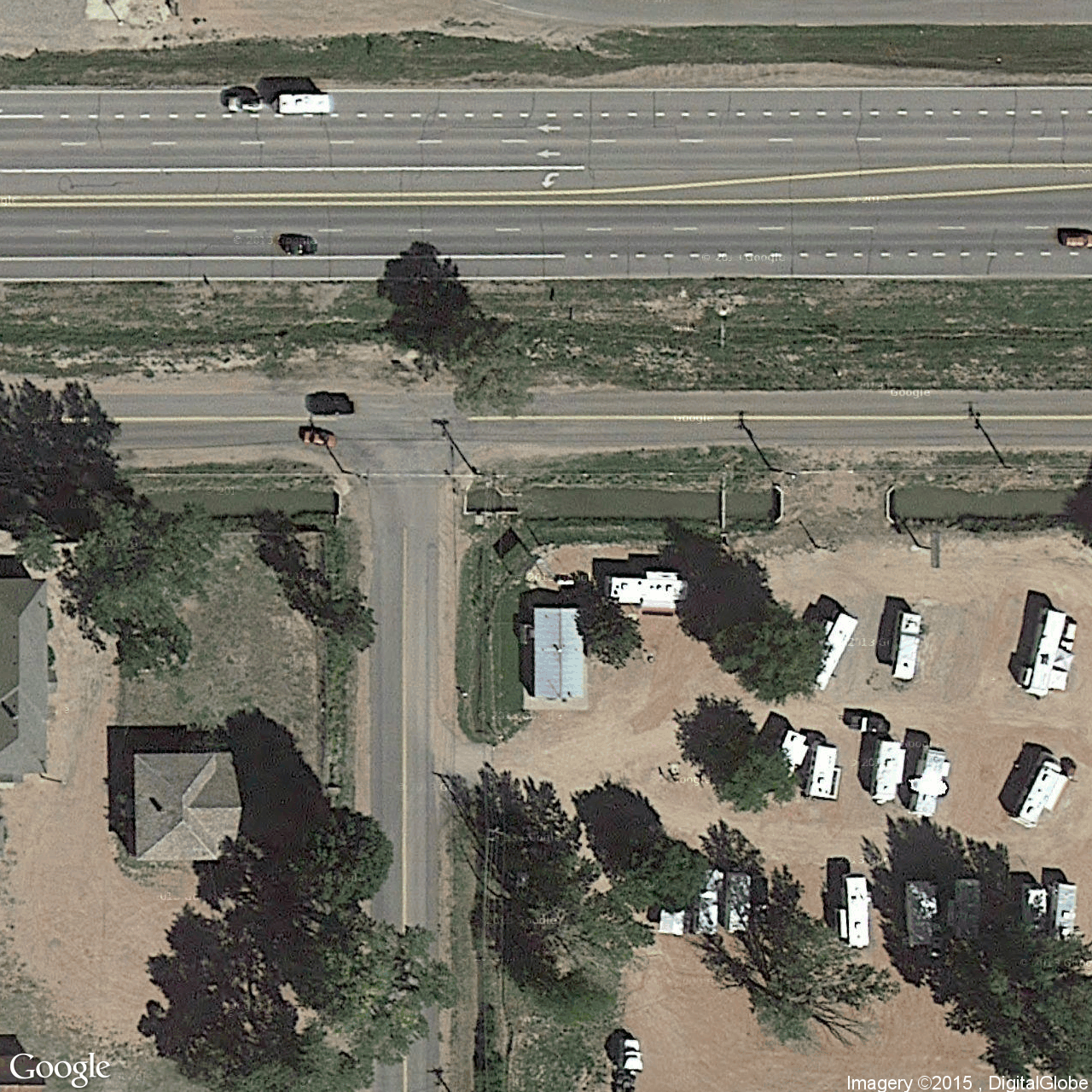

Data artist Josh Begley’s new project, “Officer Involved,” uses databases on police brutality compiled by the Guardian to present the problem in a new way. Begley’s project (like several others he has done) is an intervention that makes visible the violence behind the way we live. “Officer Involved” reveals the lack of innocence in the landscape, and, without sensationalism or sentimentality, challenges us to think about a deep injustice that so many of us accept as normal.

In row after row, we see photographs of corners, streets, suburbs, towns, all in daylight, almost all free of human presence. All these images—in spite of the mysterious lyric beauty of some of them—were captured indiscriminately by the all-seeing eye of Google, either with a bird’s eye view or at street level. They were then selected and set into an array by Begley. In one sense, they are the same as any other stills randomly pulled from Google Maps. But when we look at these photographs in particular, we are also seeing the last thing that some other human being saw. It is an immersion in the environment of someone’s last moments.

If it is true, as our ancestors always suspected, that the dead continue to exert some influence on the places where they lived and died, then Begley’s photographic project makes that insight manifest.

How quiet these scenes are, how charged by a crisp light and brilliant clarity. They look like insignificant places, but all of them are full of significance for those whose loved ones died there. All are sites of premature death, all are sites where someone was killed, and most also index an unrestituted crime.

The American landscape is thickening with these incidents. If extra-judicial killing was always facile, the reporting of it is becoming so as well. This is the value of Begley’s project: to shift us into a sober space, a space of contemplation. It is important to have the numbers, but it is vital to have an affective intervention like this one as well, which shows us how difficult the current dispensation is to bear, and how it marks us, the streets on which we move, the places in which we live.

Data artist Josh Begley’s new project, “Officer Involved,” uses databases on police brutality compiled by the Guardian to present the problem in a new way. Begley’s project (like several others he has done) is an intervention that makes visible the violence behind the way we live. “Officer Involved” reveals the lack of innocence in the landscape, and, without sensationalism or sentimentality, challenges us to think about a deep injustice that so many of us accept as normal.

In row after row, we see photographs of corners, streets, suburbs, towns, all in daylight, almost all free of human presence. All these images—in spite of the mysterious lyric beauty of some of them—were captured indiscriminately by the all-seeing eye of Google, either with a bird’s eye view or at street level. They were then selected and set into an array by Begley. In one sense, they are the same as any other stills randomly pulled from Google Maps. But when we look at these photographs in particular, we are also seeing the last thing that some other human being saw. It is an immersion in the environment of someone’s last moments.

If it is true, as our ancestors always suspected, that the dead continue to exert some influence on the places where they lived and died, then Begley’s photographic project makes that insight manifest.

How quiet these scenes are, how charged by a crisp light and brilliant clarity. They look like insignificant places, but all of them are full of significance for those whose loved ones died there. All are sites of premature death, all are sites where someone was killed, and most also index an unrestituted crime.

The American landscape is thickening with these incidents. If extra-judicial killing was always facile, the reporting of it is becoming so as well. This is the value of Begley’s project: to shift us into a sober space, a space of contemplation. It is important to have the numbers, but it is vital to have an affective intervention like this one as well, which shows us how difficult the current dispensation is to bear, and how it marks us, the streets on which we move, the places in which we live.

No comments:

Post a Comment