Each year officially since 1979 we have used the month of August to focus on the oppressive treatment of our brothers and sisters disappeared inside the state run gulags and concentration camps America calls prisons. It is during this time that we concentrate our efforts to free our mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, uncles, aunts, and all other captive family and friends who have been held in isolation for decade after decade beyond their original sentence. Many of these individuals are held in the sensory deprivation and mind control units called Security Housing Units (S.H.U. Program), without even the most basic of human rights." - BAOC

Black August is a month of great commemorative significance for the Afrikan peoples of the Diaspora, particularly those in the U.S. and especially the California prison isolation units, where the commemorative tradition originated. Black August, as noted by one our most dedicated New Afrikan Freedom Fighters, Mumia Abu-Jamal," is a month of divine meaning, of repression and radical resistance, of injustice and divine justice; of repression and righteous rebellion; of individual and collective efforts to free the slaves and break the chains that bind us".

THE ROOTS OF BLACK AUGUST

Black August originated in the concentration camps (prisons) of California in 1979 and its' roots come from the history of resistance by Black/New African/African brothers in those prisons. It's original purpose is to honor and commemorate the lives and deaths of several fallen Freedom Fighters, amongst them were Jonathan Jackson, George Jackson, W.L. Nolan, James McClain, William Christmas and Khatari Gaulden; to bring education and awareness to family members, friends, associates and communites about the conditions for the Black/New Afrikan prisoners held within those concentration camps (in particular in California) and to educate our people about and honor the history and actions of continued resistance of Black/New Afrikan/Afrikan peoples to oppression, colonization and slavery in the U.S. and throughout the Diaspora, with particular emphasis on freedom fighters and historical acts of resistance.

|

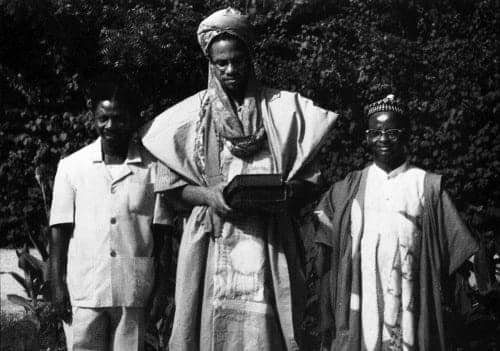

| Young Jonathan Jackson (left) at the Marin County Courthouse 7 August 1970 |

George Jackson was assassinated on August 21, 1971 by San Quentin prison guards. The assassination was a deliberate move on behalf of the US government to eliminate the revolutionary leadership of George Jackson. In the midst of the governments set up orchestrated to murder George, three prison guards were killed in a counter rebellion. The government charged six Black and Latino prisoners with the guard's deaths. These six brothers became known as the San Quentin Six (who were later acquitted of all charges).

Khatari Gaulden, one of the key intellectual architects of the Black August commemorative tradition, was murdered by the malicious intent of the government to deny him medical treatment following a mysterious accident on the San Quentin Prison yard August 1, 1978.

THE ORIGINS:

To honor these fallen soldiers and the revolutionary vision and

principles they embodied, brothers throughout the prison camps of

California united together to continue their revolutionary work. The

brothers and their family members, friends and supporters who

participated in the collective founding of Black August wore black

armbands on their left arm and studied revolutionary works, particularly

those of Comrade George Jackson. During the month of August the

brothers did not listen to the radio or watch television. Additionally,

they didn't eat or drink anything from sun-up to sundown; and loud and

boastful behavior was not allowed. Support for the prison's canteen was

also disavowed. The use of drugs and alcoholic beverages was prohibited

and the brothers held daily exercises to sharpen their minds, bodies,

and spirits in honor of the collective principles of self-sacrifice,

inner fortitude and revolutionary discipline needed to advance the New

Afrikan struggle for self-determination and freedom. Black August is

therefore a commemorative time to embrace the principles of communion,

unity, self-sacrifice, political education, physical training and

determined resistance. A select few community members joined them in

solidarity. The intent among those who commemorated and practiced Black

August was to createl revolutionary consciousness and encourage the

spirit of resistance among themselves and our communities.

To honor these fallen soldiers and the revolutionary vision and

principles they embodied, brothers throughout the prison camps of

California united together to continue their revolutionary work. The

brothers and their family members, friends and supporters who

participated in the collective founding of Black August wore black

armbands on their left arm and studied revolutionary works, particularly

those of Comrade George Jackson. During the month of August the

brothers did not listen to the radio or watch television. Additionally,

they didn't eat or drink anything from sun-up to sundown; and loud and

boastful behavior was not allowed. Support for the prison's canteen was

also disavowed. The use of drugs and alcoholic beverages was prohibited

and the brothers held daily exercises to sharpen their minds, bodies,

and spirits in honor of the collective principles of self-sacrifice,

inner fortitude and revolutionary discipline needed to advance the New

Afrikan struggle for self-determination and freedom. Black August is

therefore a commemorative time to embrace the principles of communion,

unity, self-sacrifice, political education, physical training and

determined resistance. A select few community members joined them in

solidarity. The intent among those who commemorated and practiced Black

August was to createl revolutionary consciousness and encourage the

spirit of resistance among themselves and our communities.THE BLACK AUGUST COMMEMORATION:

The tradition of fasting, studying and educatngy during Black August was

developed to help instill self-discipline amongst its' observers. The

fast is also intended to serve as a constant reminder of the sacrifices

of our fallen Freedom Fighters and the ongoing oppression of our people.

The commemorative fast is from sunrise to sunset (generally from 6:00

am to 8:00 pm). The fast includes refraining from drinking liquids and

eating food of any kind. The meal to break the fast is shared whenever

possible among comrades. Other forms of sacrifice are also encouraged to

teach self-discipline and self-reflection, such as abstaining from sex

or needless consumption (i.e. drug and alcohol use), refraining from

listening to the corporate radio and watching corporate television .

People are also encouraged to refrain from patronizing and using

corporate businesses, gas stations, department stores, supermarkets and

grocery stores. Traditionally a "Peoples' Feast" is held on August 31st

to honor the fallen and acknowledge our collective sacrifices for the

greater good.

The tradition of fasting, studying and educatngy during Black August was

developed to help instill self-discipline amongst its' observers. The

fast is also intended to serve as a constant reminder of the sacrifices

of our fallen Freedom Fighters and the ongoing oppression of our people.

The commemorative fast is from sunrise to sunset (generally from 6:00

am to 8:00 pm). The fast includes refraining from drinking liquids and

eating food of any kind. The meal to break the fast is shared whenever

possible among comrades. Other forms of sacrifice are also encouraged to

teach self-discipline and self-reflection, such as abstaining from sex

or needless consumption (i.e. drug and alcohol use), refraining from

listening to the corporate radio and watching corporate television .

People are also encouraged to refrain from patronizing and using

corporate businesses, gas stations, department stores, supermarkets and

grocery stores. Traditionally a "Peoples' Feast" is held on August 31st

to honor the fallen and acknowledge our collective sacrifices for the

greater good.Early on, the Black August practice and tradition also observed not only the sacrifices of the brothers in California's concentration camps, but to commemorate the acts of rebellion and resistance that occurred within the California Prison Camps and by other Black/New Afrikan prisoners, prisoners of war and freedom fighters. Within the first year(s) of Black August the sacrifices and struggles of our ancestors against white supremacy, colonialism, and imperialism were also included in the observation.

It must be clear that the purpose of Black August as created by the founders was not to celebrate, but to observe by individual and collective fasting, studying, educating and community work, as well as political and cultural edutainment. Black August is a time to engage in self-reaffirming action to advance our struggle for self-determination and national liberation, and to commemorate actions of resistance, revolution and rebellion while promoting an understanding and awareness of active and proactive acts of resistance. During Black August the community is encouraged to join in the observation and commemoration. Not only are the actions of self-discipline suggested, but also community members and community organizations are encouraged to come together, study and educate one another about resistance and liberation past and present through studying, discussion, reading, DVD sharing, cultural edutainment, exercising, training and breaking fast together. Black August study groups are encouraged.

It is suggested to write and/or visit someone in prison, to fund raise for and donate to the prisoners, political prisoners and prisoners of war. To observe and commemorate Black August each individual is encouraged to:

Drink only water for a suggested prolonged period or if really disciplined until after sunset from the 1st until the 31st (Suggested hours are 8am to 6pm);

Eat only one meal a day after sunset; On days called flea days, (1st, 7th, 13th and 21st), fast 24 hours until next sunset.

Work out an exercise routine for each day either individually or in groups.

Do not use any drugs, mind altering herbs or alcoholic beverages during the entire month.

Do not go to any corporate store for anything other than medical or health related items.

Do not patronize fast food establishments or vendors.

Eat healthy, natural and nutritious foods and meals.

Observe Black August through educational study groups, events and commemorations.

In the early 1980's under the leadership and practice of the Black August Organizing Committee (BAOC), the observance and practice of Black August spread from the concentration camps of California and began being practiced by Black/New Afrikan revolutionaries throughout the country . In alliance with the BAOC, members of the New Afrikan Independence Movement (NAIM) began practicing and spreading Black August during this period. The Malcolm X Grassroots Movement (MXGM) inherited knowledge and practice of Black August from its parent organization, the New Afrikan People's Organization (NAPO). MXGM began introducing the Hip-Hop "generation" to Black August in the late 1990's after being inspired by the Cuban based New Afrikan political exile Nehanda Abiodun to start "Black August Hip Hop" benefit concerts to raise awareness about our captured and exiled Freedom Fighters, our Political Prisoners, Prisoners of War, and Political Exiles like Hugo Pinell, Ruchel Magee, Mutulu Shakur, Sundiata Acoli, Sekou Odinga, the NY 3, the Move 9, Assata Shakur, and dozens more. The benefits from these political/cultural events go to the political prisoner's and their legal funds.

In the spirit of Black August organizations are encouraged to have political, cultural and educational events and not celebrations or parties. Commemoration and observance is a totally different action than celebration and partying. Black August was designed and brought to our communities to educate, agitate and activate the spirit of revolution, resistance and rebellion in our people.

Along with the Black August Organizing Committee, MXGM other organizations and individuals are now observing and commemorating Black August all over the U.S. and the Diaspora including Oakland, New York, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Atlanta, Los Angeles, Houston,Dallis, Austin, New Orleans, Cuba, Venezuela, Haiti, Tanzania, South Africa and Brazil.

A sampling of the "righteous rebellion" and "racist repression" that define this commemorative month include:

• The arrival of the first enslaved Afrikans to Jamestown, Virginia in August 1619;

• The start of the great Haitian revolution in August 1791;

• Gabriel Prosser's rebellion of August 30th, 1800.;

• The rebellion of Nat "the Prophet" Turner on August 21st, 1831;

• The call for a general strike by enslaved New Afrikans by Henry Highland Garnett on August 22nd, 1843;

• The initiation of the major network that conducted the Underground Railroad on August 2, 1850;

• The March on Washington on August 28th, 1963;

• The Watts rebellion of August 1965;

• The defense of the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika (PG – RNA) from a FBI assault in Mississippi on August 18, 1971;

• The bombing of the MOVE family by Philadelphia police on August 8, 1978.

Black August is also a commemorative month of birth and transition. Dr. Mutulu Shakur (New Afrikan prisoner of war), Pan-Africanist Leader Marcus Garvey, Maroon Russell Shoatz (political prisoner) and Chicago Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton were born in August. The great New Afrikan revolutionary scholar and theoretician W.E.B. Dubois died in Ghana on August 27, 1963. Khatari Gant the son of Original Black August Organizing Committee Members Mama Ayanna and Shaka At-Thinnin was murdered on August 4, 2007.

REMEMBER THE MONTH OF BLACK AUGUST; BLACK AUGUST RESISTANCE!

References:

Portions of this writing were taken from historical articles written by:

The Original Black August Organizing Committee

The Malcolm X Grassroots Movement

Mama Ayanna

Shaka At-Thinnin

Javad Jahi

HEALTH NOTE: IF YOU HAVE HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE OR PRE-HYPERTENSIVE; IF YOU ARE A DIABETIC OR PRE-DIABETIC; IF YOU HAVE A SERIOUS ILLNESS THAT NECESSITATES THAT YOU TAKE MEDICATIONS; IF YOU HAVE ONGOING PROBLEMS WITH YOUR KIDNEYS, BLADDER OR LIVER, DO NOT ABSTAIN FROM DRINKING WATER, DO NOT FAST FROM SUNRISE TO SUNSET! Instead, drink plenty of water and vegetable juices and eat small meals consisting of fresh fruit and vegetables and raw salads during the day so that you keep yourself nourished, sustained and healthy.