Luiz Pinto, who has been fighting eviction for decades, at home with his dog. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

When Luiz Pinto was growing up, his parents wouldn't let the family talk about slavery. The issue raised ugly memories.

Pinto’s grandmother was born into slavery. She threw herself into a river before Pinto was born, taking her own life after the son of a wealthy, white landowner raped her. The subjects of slavery and racism became taboo in the Pinto household, a sprawling set of orange brick homes perched on a hilltop where Rio de Janeiro’s famed statue of Christ the Redeemer is visible in the distance through the trees.

“I only knew her from photographs,” says Pinto, a 72-year-old samba musician.

These days, Brazil’s legacy of slavery takes up much of Pinto’s time. He travels across the state of Rio de Janeiro and back and forth to the capital in Brasília, more than 700 miles away, to lobby for the land rights of people who live in communities said to be founded by runaway slaves. Such communities are known in Portuguese as “quilombos.” According to Brazilian law, residents of quilombos have a constitutional right to land settled by their ancestors -- and that right, though rarely fulfilled, is quietly revolutionizing the country’s race relations.

In the past year, as all eyes turned toward Brazil in anticipation of the World Cup, international media offered ample coverage of the country’s staggering inequality. Reports have highlighted the stark contrast between Brazil’s hardscrabble slums and its glittering soccer stadiums. What has received less attention is the civil rights movement gradually gaining momentum throughout the country.

Brazil imported more slaves from Africa between the 16th and 19th centuries than any other country in the Americas. In 1889, it became the last nation in the Western Hemisphere to outlaw the institution. Today, more people of African descent live in Brazil than in any country in the world besides Nigeria. People of color make up 51 percent of Brazil’s population, according to the most recent census.

By and large, black Brazilians live in the worst housing and attend the poorest schools. They work the lowest-paid jobs, and they disproportionately fill the jail cells of the world’s fourth largest prison system. This lopsided state of affairs, Afro-Brazilian intellectuals and the country’s social scientists largely agree, is a result of racial discrimination with roots in the country’s history of slavery.

Brazil has never experienced anything akin to the U.S. civil rights movement or South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle. But the quilombo movement, while still in its infancy, is challenging Brazil’s deeply ingrained racial inequality. Ratified in 1988 after a two-decade-long military dictatorship, Brazil’s constitution states that residents of quilombos are entitled to a permanent, non-transferable title to the land they occupy -- something analogous to the United States’ Native American reservations, minus the self-government.

Now, more than 1 million black Brazilians are calling upon the government to honor their constitutional right to land. Among them are Luiz Pinto and his family, who have fended off decades of eviction attempts and managed to remain ensconced in their quilombo, known as Sacopã, in a neighborhood gentrified long ago by wealthier, whiter Brazilians.

The situation in Brazil stands in stark contrast to that of the United States, where, as the author Ta-Nehisi Coates pointed out in a widely read cover story for The Atlantic this May, Congress has repeatedly refused to pass a bill calling for a simple public study on the impact reparations would have on the descendants of slaves. The idea that the U.S. government would even consider handing thousands of tracts of land to black communities is unthinkable.

Few Brazilian conservatives find the idea appealing, either. Many of them have scorned the quilombo movement as an affront to property rights and have tried to overturn the law in court. And despite drafting the quilombo law in the first place, the Brazilian government has been so slow to hand over land titles to the communities in question that many applicants wonder if they’ll ever receive them.

Though they face an uncertain future, Brazil’s quilombos nevertheless contain the seeds of what may well become the most ambitious slavery reparations program ever attempted.

Pinto’s grandmother was born into slavery. She threw herself into a river before Pinto was born, taking her own life after the son of a wealthy, white landowner raped her. The subjects of slavery and racism became taboo in the Pinto household, a sprawling set of orange brick homes perched on a hilltop where Rio de Janeiro’s famed statue of Christ the Redeemer is visible in the distance through the trees.

“I only knew her from photographs,” says Pinto, a 72-year-old samba musician.

These days, Brazil’s legacy of slavery takes up much of Pinto’s time. He travels across the state of Rio de Janeiro and back and forth to the capital in Brasília, more than 700 miles away, to lobby for the land rights of people who live in communities said to be founded by runaway slaves. Such communities are known in Portuguese as “quilombos.” According to Brazilian law, residents of quilombos have a constitutional right to land settled by their ancestors -- and that right, though rarely fulfilled, is quietly revolutionizing the country’s race relations.

In the past year, as all eyes turned toward Brazil in anticipation of the World Cup, international media offered ample coverage of the country’s staggering inequality. Reports have highlighted the stark contrast between Brazil’s hardscrabble slums and its glittering soccer stadiums. What has received less attention is the civil rights movement gradually gaining momentum throughout the country.

Brazil imported more slaves from Africa between the 16th and 19th centuries than any other country in the Americas. In 1889, it became the last nation in the Western Hemisphere to outlaw the institution. Today, more people of African descent live in Brazil than in any country in the world besides Nigeria. People of color make up 51 percent of Brazil’s population, according to the most recent census.

By and large, black Brazilians live in the worst housing and attend the poorest schools. They work the lowest-paid jobs, and they disproportionately fill the jail cells of the world’s fourth largest prison system. This lopsided state of affairs, Afro-Brazilian intellectuals and the country’s social scientists largely agree, is a result of racial discrimination with roots in the country’s history of slavery.

Brazil has never experienced anything akin to the U.S. civil rights movement or South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle. But the quilombo movement, while still in its infancy, is challenging Brazil’s deeply ingrained racial inequality. Ratified in 1988 after a two-decade-long military dictatorship, Brazil’s constitution states that residents of quilombos are entitled to a permanent, non-transferable title to the land they occupy -- something analogous to the United States’ Native American reservations, minus the self-government.

Now, more than 1 million black Brazilians are calling upon the government to honor their constitutional right to land. Among them are Luiz Pinto and his family, who have fended off decades of eviction attempts and managed to remain ensconced in their quilombo, known as Sacopã, in a neighborhood gentrified long ago by wealthier, whiter Brazilians.

The situation in Brazil stands in stark contrast to that of the United States, where, as the author Ta-Nehisi Coates pointed out in a widely read cover story for The Atlantic this May, Congress has repeatedly refused to pass a bill calling for a simple public study on the impact reparations would have on the descendants of slaves. The idea that the U.S. government would even consider handing thousands of tracts of land to black communities is unthinkable.

Few Brazilian conservatives find the idea appealing, either. Many of them have scorned the quilombo movement as an affront to property rights and have tried to overturn the law in court. And despite drafting the quilombo law in the first place, the Brazilian government has been so slow to hand over land titles to the communities in question that many applicants wonder if they’ll ever receive them.

Though they face an uncertain future, Brazil’s quilombos nevertheless contain the seeds of what may well become the most ambitious slavery reparations program ever attempted.

Luiz Pinto at home in quilombo Sacopã. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

Palm

trees and towering condominiums flank the cobblestone road that leads

to quilombo Sacopã. New Kias and Volkswagens line the street, while

gated parking lots protect more valuable SUVs. Virtually none of the

residents of this section of Rio de Janeiro’s Lagoa neighborhood, with

the exception of the Pinto family, are black.

There was a time when only black people lived on the forested hillsides of Sacopã, huddled together in makeshift houses of mud and bamboo. Pinto’s grandparents traveled to the city by river with roughly 150 other ex-slaves in the late 19th century, he says, and settled among the local indigenous people, far away from the bustling city center to the north or the middle-class residential areas that would later envelop them.

“The quilombos became favelas,” Pinto says, referring to the slums that surround Rio and many other major Brazilian cities.

Developers razed much of Sacopã in the 1970s, when Rio’s growing middle and upper classes pushed into the neighborhood and sent land values skyrocketing. Local authorities expelled or relocated virtually all the black residents, most of whom were considered squatters, from Sacopã’s hillsides, clearing the way for high-rise condominiums populated by wealthier, paler-skinned Brazilians.

Pinto’s nephew, José Claudio, now 50, was 12 years old the first time the authorities visited quilombo Sacopã and threatened to kick the family out because they couldn’t prove ownership of the land. Two military police trucks rolled into the driveway. The cops said the family’s houses would be demolished.

A lucky connection allowed the Pinto family to escape eviction. It happened that the family’s lawyer was married to a high-ranking military officer. In the days of Brazil’s military dictatorship, which lasted from 1964 to 1985, the order of a general carried far more weight than a stack of legal documents.

“I’ll never forget it,” José Claudio told The Huffington Post. “The subtenente, or whoever was in charge of the troops, saluted him and he said: ‘No one’s getting kicked out of here.’ That was our first victory.”

The security afforded by the family’s loose connection to the general lasted only as long as the military dictatorship itself. In 1986, a year after Brazil’s return to democracy, the cops came back to Sacopã, and this time they stayed. For one year, local authorities stationed two round-the-clock policemen outside Sacopã and locked the kitchen shut to keep the Pinto family from hosting parties or playing live music.

“They chained us up here,” José Claudio said, rattling a rusted lock that still dangles from the kitchen window. “We couldn’t do anything.”

Today, visitors to the neighborhood might not even notice the Pinto family’s cluster of houses, hidden behind a towering condo, if not for the sign in the driveway declaring the community’s constitutionally protected status as a quilombo.

The property received quilombo certification in 2004 after undergoing a lengthy application process with the federal government. Instead of trying to kick them out, the authorities now guarantee the group’s right to stay while the government carries out the work of demarcating the land. Still, as is the case with the vast majority of Brazil’s quilombos, a complicated bureaucratic system has prevented the Pintos from receiving the title to their land.

“Nothing happens,” Pinto says. “The headway we’ve made for quilombo land rights in this country is practically nil.”

Without a land title, the Pintos live in a state of limbo, the threat of eviction looming constantly.

There was a time when only black people lived on the forested hillsides of Sacopã, huddled together in makeshift houses of mud and bamboo. Pinto’s grandparents traveled to the city by river with roughly 150 other ex-slaves in the late 19th century, he says, and settled among the local indigenous people, far away from the bustling city center to the north or the middle-class residential areas that would later envelop them.

“The quilombos became favelas,” Pinto says, referring to the slums that surround Rio and many other major Brazilian cities.

Developers razed much of Sacopã in the 1970s, when Rio’s growing middle and upper classes pushed into the neighborhood and sent land values skyrocketing. Local authorities expelled or relocated virtually all the black residents, most of whom were considered squatters, from Sacopã’s hillsides, clearing the way for high-rise condominiums populated by wealthier, paler-skinned Brazilians.

Pinto’s nephew, José Claudio, now 50, was 12 years old the first time the authorities visited quilombo Sacopã and threatened to kick the family out because they couldn’t prove ownership of the land. Two military police trucks rolled into the driveway. The cops said the family’s houses would be demolished.

A lucky connection allowed the Pinto family to escape eviction. It happened that the family’s lawyer was married to a high-ranking military officer. In the days of Brazil’s military dictatorship, which lasted from 1964 to 1985, the order of a general carried far more weight than a stack of legal documents.

“I’ll never forget it,” José Claudio told The Huffington Post. “The subtenente, or whoever was in charge of the troops, saluted him and he said: ‘No one’s getting kicked out of here.’ That was our first victory.”

The security afforded by the family’s loose connection to the general lasted only as long as the military dictatorship itself. In 1986, a year after Brazil’s return to democracy, the cops came back to Sacopã, and this time they stayed. For one year, local authorities stationed two round-the-clock policemen outside Sacopã and locked the kitchen shut to keep the Pinto family from hosting parties or playing live music.

“They chained us up here,” José Claudio said, rattling a rusted lock that still dangles from the kitchen window. “We couldn’t do anything.”

Today, visitors to the neighborhood might not even notice the Pinto family’s cluster of houses, hidden behind a towering condo, if not for the sign in the driveway declaring the community’s constitutionally protected status as a quilombo.

The property received quilombo certification in 2004 after undergoing a lengthy application process with the federal government. Instead of trying to kick them out, the authorities now guarantee the group’s right to stay while the government carries out the work of demarcating the land. Still, as is the case with the vast majority of Brazil’s quilombos, a complicated bureaucratic system has prevented the Pintos from receiving the title to their land.

“Nothing happens,” Pinto says. “The headway we’ve made for quilombo land rights in this country is practically nil.”

Without a land title, the Pintos live in a state of limbo, the threat of eviction looming constantly.

José

Claudio Pinto holds the lock that was once used to keep the windows of

quilombo Sacopã's kitchen shut. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

Most

Brazilians familiar with the term “quilombo” associate it with the

country's past rather than its present. The word has been in use for

hundreds of years, dating back to the colonial period -- roughly the

sixteenth century through 1825 -- when runaway slave settlements dotted

the Brazilian countryside. The most famous of those settlements,

Palmares, grew to more than 15,000 inhabitants and lasted nearly a

century before the Portuguese destroyed it in 1694.

Though the term faded from use during the early 20th century, by the 1950s, advocates trying to lend momentum to a nascent black Brazilian civil rights effort began to resurrect it.

The symbolic power of the quilombo appealed to former Congresswoman Benedita da Silva. In 1986, after Brazil’s military dictatorship ended, da Silva was one of 11 Afro-Brazilians among the 594 members of Congress elected to draw up the country’s new founding document. She managed to convince a body of lawmakers composed largely of light-skinned men to lay the framework for a modern-day, Brazilian version of “40 acres and a mule.”

Under da Silva’s law, quilombo members own their land outright. They pay no rent and no one, no matter how rich, can legally kick them out (with the exception of the federal government, which is currently fighting eminent domain battles in the courts with at least two certified quilombos, whose respective claims overlap a Navy base and a space station).

The key to da Silva’s success was the law’s innocuous phrasing. It specifies that descendants of residents of the quilombos have a right to a permanent title to the land they occupy. But the term “quilombo” was left legally undefined for years, implying that it would be necessary for any such community to be able to trace its direct lineage to a runaway slave settlement. Most of the assembly members who voted for da Silva’s article likely viewed it as a symbolic gesture that would affect only a handful of communities.

It didn’t work out that way. In 2003, the left-wing government of President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva expanded the legal definition of the term “quilombo,” issuing a presidential decree that categorized quilombo descendants as an ethnicity. Under Brazilian law, people have the right to define their own ethnicity for the purposes of social policy. With Lula’s new rule, virtually any black community could become certified as a quilombo if a majority of its residents decided to.

When Lula’s decree was issued in 2003, there were 29 recognized quilombos in Brazil. As of 2013, that number had swelled to more than 2,400, comprising more than 1 million people, with hundreds more communities applying that have yet to be recognized.

The government has certified quilombos in all but two of Brazil’s 26 states, from the tropical north to the industrialized south. There are quilombos that encompass thousands of people and quilombos that consist of just a few extended families. There are quilombos in the cities, quilombos along the countryside, quilombos on islands and quilombos in the rainforest. The land claimed by these communities totals about 4.4 million acres, according to the Brazilian federal government -- an area roughly the size of New Jersey.

Asked if she knew her proposal would be applied so extensively, da Silva said that was always her intention.

“Of course -- that’s what we were working for,” da Silva told HuffPost. “[The article] wasn’t born just because I was at the Constitutional Assembly. It was born because there existed and continues to exist a black movement that includes academics, includes quilombolas, the universities -- all dedicated to validating black people’s land rights.”

Yet the Brazilian government has shown little sign that it will deliver the land titles promised by the constitution any time soon. Itamar Rangel of the National Institute for Colonization and Land Reform, the federal agency that carries out quilombo land titling, says the constant delays owe to the necessity of negotiating a settlement and indemnification with property holders. “Brazilian law defends the property rights of any citizen,” Rangel told HuffPost. “Carrying out this policy won’t be cheap.”

As of this year, only 217 quilombos have received land titles. The Brazilian government issued only three land titles in 2013, and another three the year before that -- the lowest annual number since 2004.

“The quilombo movement is poorly prepared,” José Arruti, an anthropologist at the State University of Campinas who studies quilombos, told HuffPost. “Their communities began to organize and to understand the political game a very short time ago.”

Though the term faded from use during the early 20th century, by the 1950s, advocates trying to lend momentum to a nascent black Brazilian civil rights effort began to resurrect it.

The symbolic power of the quilombo appealed to former Congresswoman Benedita da Silva. In 1986, after Brazil’s military dictatorship ended, da Silva was one of 11 Afro-Brazilians among the 594 members of Congress elected to draw up the country’s new founding document. She managed to convince a body of lawmakers composed largely of light-skinned men to lay the framework for a modern-day, Brazilian version of “40 acres and a mule.”

Under da Silva’s law, quilombo members own their land outright. They pay no rent and no one, no matter how rich, can legally kick them out (with the exception of the federal government, which is currently fighting eminent domain battles in the courts with at least two certified quilombos, whose respective claims overlap a Navy base and a space station).

The key to da Silva’s success was the law’s innocuous phrasing. It specifies that descendants of residents of the quilombos have a right to a permanent title to the land they occupy. But the term “quilombo” was left legally undefined for years, implying that it would be necessary for any such community to be able to trace its direct lineage to a runaway slave settlement. Most of the assembly members who voted for da Silva’s article likely viewed it as a symbolic gesture that would affect only a handful of communities.

It didn’t work out that way. In 2003, the left-wing government of President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva expanded the legal definition of the term “quilombo,” issuing a presidential decree that categorized quilombo descendants as an ethnicity. Under Brazilian law, people have the right to define their own ethnicity for the purposes of social policy. With Lula’s new rule, virtually any black community could become certified as a quilombo if a majority of its residents decided to.

When Lula’s decree was issued in 2003, there were 29 recognized quilombos in Brazil. As of 2013, that number had swelled to more than 2,400, comprising more than 1 million people, with hundreds more communities applying that have yet to be recognized.

The government has certified quilombos in all but two of Brazil’s 26 states, from the tropical north to the industrialized south. There are quilombos that encompass thousands of people and quilombos that consist of just a few extended families. There are quilombos in the cities, quilombos along the countryside, quilombos on islands and quilombos in the rainforest. The land claimed by these communities totals about 4.4 million acres, according to the Brazilian federal government -- an area roughly the size of New Jersey.

Asked if she knew her proposal would be applied so extensively, da Silva said that was always her intention.

“Of course -- that’s what we were working for,” da Silva told HuffPost. “[The article] wasn’t born just because I was at the Constitutional Assembly. It was born because there existed and continues to exist a black movement that includes academics, includes quilombolas, the universities -- all dedicated to validating black people’s land rights.”

Yet the Brazilian government has shown little sign that it will deliver the land titles promised by the constitution any time soon. Itamar Rangel of the National Institute for Colonization and Land Reform, the federal agency that carries out quilombo land titling, says the constant delays owe to the necessity of negotiating a settlement and indemnification with property holders. “Brazilian law defends the property rights of any citizen,” Rangel told HuffPost. “Carrying out this policy won’t be cheap.”

As of this year, only 217 quilombos have received land titles. The Brazilian government issued only three land titles in 2013, and another three the year before that -- the lowest annual number since 2004.

“The quilombo movement is poorly prepared,” José Arruti, an anthropologist at the State University of Campinas who studies quilombos, told HuffPost. “Their communities began to organize and to understand the political game a very short time ago.”

A sign in at the entrance to Sacopã announces the community's quilombo status. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

A

guitarist and singer with several records under his belt and a

following in Rio, Pinto inherited his vocation from his parents. His

father played the cavaquinho, a ukulele variation often used in samba,

Brazil’s national music, which evolved out of rhythms brought to the

country by African slaves. The songs his mother sang as she hung the

laundry to dry remain etched in Pinto’s head.

“She was a domestic artist,” Pinto said, smiling as he recalled a tune his mother wrote about the U.S. moon landing in 1969. “I’ve got a lot of her songs in my repertoire that I play at my shows. She didn’t have the courage to record."

Music has helped Pinto’s land fight in more ways than one. To receive certification as a quilombo, every community must pass through a multi-step process involving three state agencies and a government-commissioned study conducted by social scientists, who document the cultural and historical characteristics that make for a quilombo-specific ethnicity. For the researchers who filed Sacopã’s anthropological report in 2007, one of those characteristics was its music.

“It’s given me a lot of strength in this struggle,” said Pinto. “Being onstage, you’re being heard by thousands of people, so you can explain your situation.”

Hear Pinto sing his mother's song above.

The heart of the Pintos’ quilombo is a covered space between the families’ houses, nestled among papaya and palm trees. Here adults gather, children play and food is served on red picnic tables bearing the logo for Itapaiva, a local beer. Some of the most legendary names in Brazilian music -- Zeca Pagodinho and Beth Carvalho among them -- have performed at the monthly parties Sacopã once hosted.

In recent years, though, the local government has squelched those parties. Neighbors in the towering buildings that flank the quilombo have complained about the noise, and said the parking lot the family sets up to earn extra cash is a violation of zoning laws that restrict businesses in the neighborhood.

The open space that once hosted famous names in Rio’s samba scene now sits idle, animated only on Sundays when the family’s 28 members sit down at the red plastic tables to an afternoon meal of feijoada, Brazil’s national dish, a stew of black beans and pork.

Pinto said it’s unfair that the neighborhood is zoned in favor of his whiter, wealthier neighbors. “The argument they always use against us is that this is a strictly residential area,” he said. “So we can’t do these things. But out there they’ve got bakeries, they’ve got bars. It’s a cowardly way for them to destabilize us so they can kick us out of here.”

“She was a domestic artist,” Pinto said, smiling as he recalled a tune his mother wrote about the U.S. moon landing in 1969. “I’ve got a lot of her songs in my repertoire that I play at my shows. She didn’t have the courage to record."

Music has helped Pinto’s land fight in more ways than one. To receive certification as a quilombo, every community must pass through a multi-step process involving three state agencies and a government-commissioned study conducted by social scientists, who document the cultural and historical characteristics that make for a quilombo-specific ethnicity. For the researchers who filed Sacopã’s anthropological report in 2007, one of those characteristics was its music.

“It’s given me a lot of strength in this struggle,” said Pinto. “Being onstage, you’re being heard by thousands of people, so you can explain your situation.”

Hear Pinto sing his mother's song above.

The heart of the Pintos’ quilombo is a covered space between the families’ houses, nestled among papaya and palm trees. Here adults gather, children play and food is served on red picnic tables bearing the logo for Itapaiva, a local beer. Some of the most legendary names in Brazilian music -- Zeca Pagodinho and Beth Carvalho among them -- have performed at the monthly parties Sacopã once hosted.

In recent years, though, the local government has squelched those parties. Neighbors in the towering buildings that flank the quilombo have complained about the noise, and said the parking lot the family sets up to earn extra cash is a violation of zoning laws that restrict businesses in the neighborhood.

The open space that once hosted famous names in Rio’s samba scene now sits idle, animated only on Sundays when the family’s 28 members sit down at the red plastic tables to an afternoon meal of feijoada, Brazil’s national dish, a stew of black beans and pork.

Pinto said it’s unfair that the neighborhood is zoned in favor of his whiter, wealthier neighbors. “The argument they always use against us is that this is a strictly residential area,” he said. “So we can’t do these things. But out there they’ve got bakeries, they’ve got bars. It’s a cowardly way for them to destabilize us so they can kick us out of here.”

Luiz

Pinto and his grandson in the area of their quilombo that once hosted

lively parties. Neighbors' complaints have since shut down the events.

(Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

Former Brazilian Senator Demóstenes Torres of the Demócraticos 25 party, or DEM, ignited a controversy in 2010

when he called Brazil’s history of racial mixing “beautiful” and

expressly denied that black women were raped during slavery, even though

rape and other forms of abuse during that era are a matter of

historical record. (Torres himself has both African and European

ancestors.)

Torres’ comments, however inaccurate, gestured toward some widespread beliefs about race in Brazil. Like the United States, Brazil built its early wealth on the backs of African slaves. But historically, interracial relationships have always occurred far more frequently in Brazil than in the U.S., and modern-day Brazil is a largely mixed-race society where the terms “black” and “white” don’t mean quite what they do in the United States.

Similarly to Latinos in the U.S., many Afro-Brazilians view race on a spectrum where skin color is measured by gradation. In 1976, when Brazil’s census first allowed survey respondents to write in their race rather than picking among the four options of white, black, “yellow” (Asian) and “pardo” (mixed race/mulatto), respondents submitted 135 different terms to describe their skin color. The dozens of self-selected shades included “chestnut,” “dark white” and “regular,” as well as descriptions like “black Indian,” “cinnamonish,” “navy blue” and “toasted.”

The Pinto family itself encompasses a panorama of blackness, with both dark-skinned members like Luiz and lighter-skinned members like José Claudio, who nevertheless identifies as black.

“My mother married a white man,” José Claudio said. “So I hear things. Sometimes white people will say, ‘Oh, that black guy,’ I don’t know what. They don’t know that I’m black too.”

Brazil’s widespread mixing of the races underpins the idea, popular in many quarters, that the country is a “racial democracy” in which members of all ethnicities live in harmony.

Social scientists and Afro-Brazilian intellectuals, on the other hand, have long viewed this idea as wishful thinking, pointing to a growing body of socioeconomic studies and statistics to bolster their case.

According to 2011 census figures, the most recent available, some 51 percent of Brazilians identify as either black or mixed-race -- terms that Brazilian statistics agencies often group together as simply “black.” Among the poorest 10 percent of the population, 72 percent are black, according to a 2012 study by the Institute of Applied Economic Research. A 2013 study by the same organization found that 70 percent of homicide victims are black, while another study from 2010 found that 60 percent of the prison population is black.

And reality may in fact be even grimmer than those numbers suggest. A revealing 2011 survey of 2,500 Brazilians led by sociologist Edward Telles asked each participant to identify his or her race and state his or her household income and level of education. At the same time, unbeknownst to the person taking the survey, the researcher would use a palette with 11 shades running from off-white to nearly black to identify the respondent’s skin tone.

Ordering the data by self-reported race yielded mixed results. White Brazilians fared better, but there was significant variation in education and income levels for Brazilians of color. Ordering the data by observed skin color, however, showed a sharp, repetitive pattern of inequality in which education and income plummet as the respondent’s skin gets darker.

“Discrimination is pretty clear,” Telles said, explaining that while Brazil never experienced explicit segregation akin to the United States, the country’s history of slavery has molded a society where racism reveals itself socioeconomically. “You wouldn’t think this is a largely black country if you just looked at advertisements and who’s on the TV screen, unless you were watching soccer. If you look at people in the stands at the World Cup, they’re almost all white. How does that compare to the people playing on the field?”

All of this is obvious to José Claudio. “When someone sees a black guy in an imported car, they say ‘Damn, he must be a soccer player or a singer!’” he said. “What was left over for black people was sports and music. No one thinks, ‘Damn, that guy must be a doctor. Maybe he’s a lawyer or a pilot.’”

Such research, however, has yet to convince many on the Brazilian right that reparations are the way to address racism. In 2004, conservative politicians who would later go on to form the DEM sued the Lula da Silva administration to overturn the presidential decree designating quilombos as an ethnicity, accusing the president of illegally bypassing Congress. (A representative DEM representative declined to comment for this article, adding that the party no longer considers the lawsuit a priority.)

By summer 2010, the lawsuit had made its way up to the country’s Supreme Justice Tribunal, where it has sat waiting for a decision ever since. The suspense weighs like an anvil on people like the Pinto family.

Meanwhile, quilombo certification and land titling continue to inch forward. But overturning Lula’s decree would likely annul them, destroying the movement overnight.

Torres’ comments, however inaccurate, gestured toward some widespread beliefs about race in Brazil. Like the United States, Brazil built its early wealth on the backs of African slaves. But historically, interracial relationships have always occurred far more frequently in Brazil than in the U.S., and modern-day Brazil is a largely mixed-race society where the terms “black” and “white” don’t mean quite what they do in the United States.

Similarly to Latinos in the U.S., many Afro-Brazilians view race on a spectrum where skin color is measured by gradation. In 1976, when Brazil’s census first allowed survey respondents to write in their race rather than picking among the four options of white, black, “yellow” (Asian) and “pardo” (mixed race/mulatto), respondents submitted 135 different terms to describe their skin color. The dozens of self-selected shades included “chestnut,” “dark white” and “regular,” as well as descriptions like “black Indian,” “cinnamonish,” “navy blue” and “toasted.”

The Pinto family itself encompasses a panorama of blackness, with both dark-skinned members like Luiz and lighter-skinned members like José Claudio, who nevertheless identifies as black.

“My mother married a white man,” José Claudio said. “So I hear things. Sometimes white people will say, ‘Oh, that black guy,’ I don’t know what. They don’t know that I’m black too.”

Brazil’s widespread mixing of the races underpins the idea, popular in many quarters, that the country is a “racial democracy” in which members of all ethnicities live in harmony.

Social scientists and Afro-Brazilian intellectuals, on the other hand, have long viewed this idea as wishful thinking, pointing to a growing body of socioeconomic studies and statistics to bolster their case.

According to 2011 census figures, the most recent available, some 51 percent of Brazilians identify as either black or mixed-race -- terms that Brazilian statistics agencies often group together as simply “black.” Among the poorest 10 percent of the population, 72 percent are black, according to a 2012 study by the Institute of Applied Economic Research. A 2013 study by the same organization found that 70 percent of homicide victims are black, while another study from 2010 found that 60 percent of the prison population is black.

And reality may in fact be even grimmer than those numbers suggest. A revealing 2011 survey of 2,500 Brazilians led by sociologist Edward Telles asked each participant to identify his or her race and state his or her household income and level of education. At the same time, unbeknownst to the person taking the survey, the researcher would use a palette with 11 shades running from off-white to nearly black to identify the respondent’s skin tone.

Ordering the data by self-reported race yielded mixed results. White Brazilians fared better, but there was significant variation in education and income levels for Brazilians of color. Ordering the data by observed skin color, however, showed a sharp, repetitive pattern of inequality in which education and income plummet as the respondent’s skin gets darker.

“Discrimination is pretty clear,” Telles said, explaining that while Brazil never experienced explicit segregation akin to the United States, the country’s history of slavery has molded a society where racism reveals itself socioeconomically. “You wouldn’t think this is a largely black country if you just looked at advertisements and who’s on the TV screen, unless you were watching soccer. If you look at people in the stands at the World Cup, they’re almost all white. How does that compare to the people playing on the field?”

All of this is obvious to José Claudio. “When someone sees a black guy in an imported car, they say ‘Damn, he must be a soccer player or a singer!’” he said. “What was left over for black people was sports and music. No one thinks, ‘Damn, that guy must be a doctor. Maybe he’s a lawyer or a pilot.’”

Such research, however, has yet to convince many on the Brazilian right that reparations are the way to address racism. In 2004, conservative politicians who would later go on to form the DEM sued the Lula da Silva administration to overturn the presidential decree designating quilombos as an ethnicity, accusing the president of illegally bypassing Congress. (A representative DEM representative declined to comment for this article, adding that the party no longer considers the lawsuit a priority.)

By summer 2010, the lawsuit had made its way up to the country’s Supreme Justice Tribunal, where it has sat waiting for a decision ever since. The suspense weighs like an anvil on people like the Pinto family.

Meanwhile, quilombo certification and land titling continue to inch forward. But overturning Lula’s decree would likely annul them, destroying the movement overnight.

A view of Rio de Janeiro from the city's famous Christ the Redeemer statue. (Jamie Squire/Getty Images)

The

view of Rio’s Christ the Redeemer statue off in the distance is much

clearer from Ana Simas’ fourth-floor apartment at the bottom of the

hill. A psychiatrist with pale skin and shoulder-length brown hair,

Simas has called the neighborhood of Lagoa home since her birth in 1952.

She seems an unlikely adversary for the Pinto family as they pursue their quilombo land claim. Simas takes pride in her progressive politics. She believes racism permeates Brazilian society. And she’s known the Pintos for decades. When she married her former husband in 1989, a samba musician named Jorge Simas, they held the wedding celebration at the Pinto family home in Sacopã.

But the friendship began to fray in 1999, the year Simas was elected head of the neighborhood homeowners association. Shortly after she took her new position, Pinto walked down to her apartment and asked her to make a statement before the court in support of his family’s land claim under Brazil’s squatter right law, which they were using at the time as a defense against authorities who were trying to evict them.

Simas refused. “It was the first time over the years that I’d known him that I sensed something odd in the way he was behaving,” she said. “It’s not up to me to decide if the land is his. It’s up to him to prove if the land is his and it’s the judge’s job to decide.”

As she took greater interest in the case, she found more reasons to oppose it. The Pinto family’s claim extends across an area designated as a nature reserve, which Simas refers to as “the lung of the Zona Sul,” Rio’s ritzy southern section. In 2005, the homeowners association joined a lawsuit filed by the Public Environmental Ministry against the Pinto family and other alleged squatters, accusing them of damaging the environment.

Simas began to doubt whether Sacopã was a quilombo at all. “I’ve never seen a quilombo that was just one family,” she said. “All the other real quilombos, like the quilombo of Jongo de Serrinha, are many families, not just one.”

Curious for information about Sacopã’s origins, she pulled the wedding certificate for Pinto’s parents from the local archives. “Neither one of them was born there,” she said, producing a photocopy of the document, which identifies the birthplace of both of Pinto’s parents as a Rio suburb called Novo Friburgo. “What were they doing being a quilombo here, if they’re from Novo Friburgo?”

She seems an unlikely adversary for the Pinto family as they pursue their quilombo land claim. Simas takes pride in her progressive politics. She believes racism permeates Brazilian society. And she’s known the Pintos for decades. When she married her former husband in 1989, a samba musician named Jorge Simas, they held the wedding celebration at the Pinto family home in Sacopã.

But the friendship began to fray in 1999, the year Simas was elected head of the neighborhood homeowners association. Shortly after she took her new position, Pinto walked down to her apartment and asked her to make a statement before the court in support of his family’s land claim under Brazil’s squatter right law, which they were using at the time as a defense against authorities who were trying to evict them.

Simas refused. “It was the first time over the years that I’d known him that I sensed something odd in the way he was behaving,” she said. “It’s not up to me to decide if the land is his. It’s up to him to prove if the land is his and it’s the judge’s job to decide.”

As she took greater interest in the case, she found more reasons to oppose it. The Pinto family’s claim extends across an area designated as a nature reserve, which Simas refers to as “the lung of the Zona Sul,” Rio’s ritzy southern section. In 2005, the homeowners association joined a lawsuit filed by the Public Environmental Ministry against the Pinto family and other alleged squatters, accusing them of damaging the environment.

Simas began to doubt whether Sacopã was a quilombo at all. “I’ve never seen a quilombo that was just one family,” she said. “All the other real quilombos, like the quilombo of Jongo de Serrinha, are many families, not just one.”

Curious for information about Sacopã’s origins, she pulled the wedding certificate for Pinto’s parents from the local archives. “Neither one of them was born there,” she said, producing a photocopy of the document, which identifies the birthplace of both of Pinto’s parents as a Rio suburb called Novo Friburgo. “What were they doing being a quilombo here, if they’re from Novo Friburgo?”

Ana

Simas, head of the Lagoa neighborhood homeowners association, opposes

Sacopã's quilombo certification. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

Simas

is not the only one with questions about what does and doesn’t

constitute a quilombo. While Brazilian law tends to assign more

importance to a group’s culture than to its history, that idea has yet

to trickle down to much of the public.

Claudio Girafa, a white, 57-year-old civil engineer who comes to Pinto’s neighborhood on weekends to watch the soccer games at his brother’s apartment, says it’s important to him that quilombos prove their historical roots. “There’s a lot of questioning in the area about whether [Sacopã] was really a quilombo community,” he said. “I’m not against the idea of preserving quilombos in principle, but I think it has to be very well proven because it affects properties that were acquired later.”

The researchers who filed Sacopã’s anthropological report confirming its quilombo status in 2007 were aware that Pinto’s parents had been born in Novo Friburgo. Pinto’s parents lived an itinerant life, traveling from town to town and farm to farm in search of work before settling in the late 1920s on the hill in Lagoa where the family lives today. Pinto’s father was one of the workers who helped construct Rua Sacopã, the road that snakes up the hill.

But Pinto maintains that his grandparents had already arrived in the approximate area by the late 19th century, taking shelter in a cave lying within territory claimed by the quilombo. And while the researchers couldn’t document the presence of Pinto’s family prior to the 1920s, they wrote that the family’s stories “seem to us very likely from the point of view of historical science.”

What mattered for the anthropologists was that the Pinto family’s collective memory pointed to the existence of a group identity informed by a history of escaping slavery -- a quilombo ethnicity.

Still, the importance of this kind of group identity can elude some Brazilians who have no personal stake in the quilombo issue. Like many citizens, when asked if Brazil is a racist country, Girafa is quick to say it’s not. But he believes that programs like the quilombo movement and other forms of affirmative action only exacerbate existing racial tensions by committing injustices against whites. “There’s still discrimination, yes,” he said. “But what’s been done has only made things worse.”

Pinto feels differently. For him, racism isn’t just about being eyed suspiciously in rich parts of town, or being told to enter through the back when he knocks on a door because people assume he’s a servant -- indignities that many black Brazilians describe experiencing.

Racism for Pinto means that his ancestors were enslaved, and that once they were freed, his grandmother was raped and his parents pushed into a slum. Racism means that after his parents turned that slum into a home, the authorities tried to make him leave, because now white people wanted to live there.

“Racism in Brazil is institutional,” Pinto said. “It’s everywhere. It’s very difficult to confront.”

For his part, Pinto hopes to use the quilombo movement to shed light on the country’s racial inequities. He said he was disappointed by the lack of Afro-Brazilian participation in the protests against government spending on the World Cup over the last year, which were largely led by light-skinned, middle-class residents.

“The quilombo movement is still very timid,” Pinto said. “We’re practically invisible to society. So if we don’t go out now and show our faces in the street, go out and protest, we’re going to be forgotten. We’re already forgotten.”

Instead, the Pinto family protests by continuing to balk in the face of eviction threats and turning down offers of millions of reais, the local currency, to abandon the place they’ve always called home.

But Pinto often feels invisible in his own neighborhood. On a recent walk with his grandson, he said, the two stopped at a plaza for a break. Looking around, Pinto noticed they were the only two black people there.

“I feel racism much more strongly because I’m in a place where only people with money live, and people with money are white,” he said. “What I understand very well is that we’re black people in a place reserved for white people.”

Claudio Girafa, a white, 57-year-old civil engineer who comes to Pinto’s neighborhood on weekends to watch the soccer games at his brother’s apartment, says it’s important to him that quilombos prove their historical roots. “There’s a lot of questioning in the area about whether [Sacopã] was really a quilombo community,” he said. “I’m not against the idea of preserving quilombos in principle, but I think it has to be very well proven because it affects properties that were acquired later.”

The researchers who filed Sacopã’s anthropological report confirming its quilombo status in 2007 were aware that Pinto’s parents had been born in Novo Friburgo. Pinto’s parents lived an itinerant life, traveling from town to town and farm to farm in search of work before settling in the late 1920s on the hill in Lagoa where the family lives today. Pinto’s father was one of the workers who helped construct Rua Sacopã, the road that snakes up the hill.

But Pinto maintains that his grandparents had already arrived in the approximate area by the late 19th century, taking shelter in a cave lying within territory claimed by the quilombo. And while the researchers couldn’t document the presence of Pinto’s family prior to the 1920s, they wrote that the family’s stories “seem to us very likely from the point of view of historical science.”

What mattered for the anthropologists was that the Pinto family’s collective memory pointed to the existence of a group identity informed by a history of escaping slavery -- a quilombo ethnicity.

Still, the importance of this kind of group identity can elude some Brazilians who have no personal stake in the quilombo issue. Like many citizens, when asked if Brazil is a racist country, Girafa is quick to say it’s not. But he believes that programs like the quilombo movement and other forms of affirmative action only exacerbate existing racial tensions by committing injustices against whites. “There’s still discrimination, yes,” he said. “But what’s been done has only made things worse.”

Pinto feels differently. For him, racism isn’t just about being eyed suspiciously in rich parts of town, or being told to enter through the back when he knocks on a door because people assume he’s a servant -- indignities that many black Brazilians describe experiencing.

Racism for Pinto means that his ancestors were enslaved, and that once they were freed, his grandmother was raped and his parents pushed into a slum. Racism means that after his parents turned that slum into a home, the authorities tried to make him leave, because now white people wanted to live there.

“Racism in Brazil is institutional,” Pinto said. “It’s everywhere. It’s very difficult to confront.”

For his part, Pinto hopes to use the quilombo movement to shed light on the country’s racial inequities. He said he was disappointed by the lack of Afro-Brazilian participation in the protests against government spending on the World Cup over the last year, which were largely led by light-skinned, middle-class residents.

“The quilombo movement is still very timid,” Pinto said. “We’re practically invisible to society. So if we don’t go out now and show our faces in the street, go out and protest, we’re going to be forgotten. We’re already forgotten.”

Instead, the Pinto family protests by continuing to balk in the face of eviction threats and turning down offers of millions of reais, the local currency, to abandon the place they’ve always called home.

But Pinto often feels invisible in his own neighborhood. On a recent walk with his grandson, he said, the two stopped at a plaza for a break. Looking around, Pinto noticed they were the only two black people there.

“I feel racism much more strongly because I’m in a place where only people with money live, and people with money are white,” he said. “What I understand very well is that we’re black people in a place reserved for white people.”

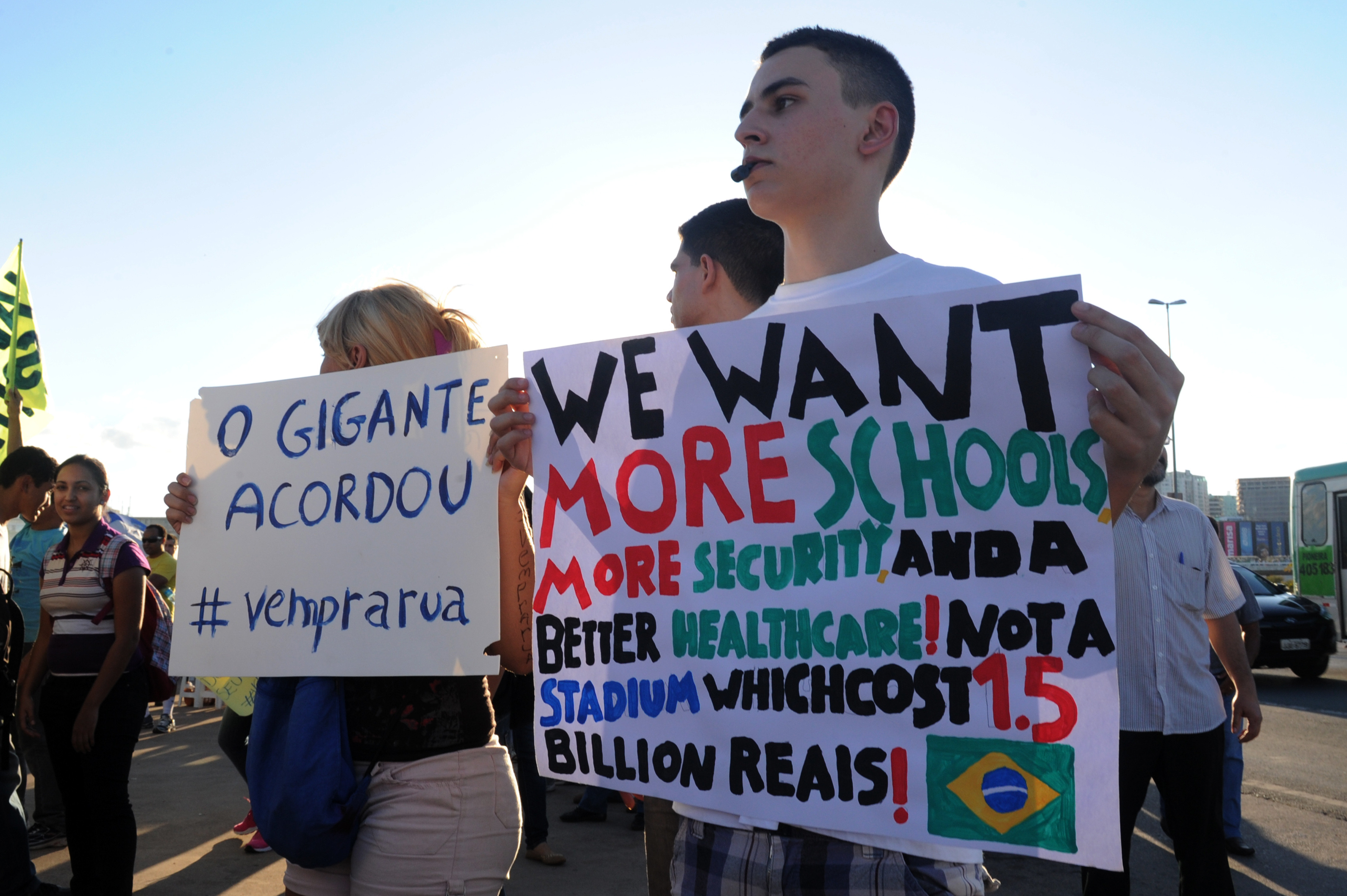

Students

hold signs during a protest demanding better public services and

criticizing massive government spending on the World Cup. Pinto said he

was disappointed by the lack of Afro-Brazilian participation in the

World Cup protests, which were largely led by light-skinned,

middle-class residents. (Evaristo Sa/Getty Images)

Students

hold signs during a protest demanding better public services and

criticizing massive government spending on the World Cup. Pinto said he

was disappointed by the lack of Afro-Brazilian participation in the

World Cup protests, which were largely led by light-skinned,

middle-class residents. (Evaristo Sa/Getty Images)

PARTII

Afro-Brazilians Demand Slavery Reparations Because 'Poverty Has A Color'

Posted:

Almir

Viera Pereira holds a handful of dry soil on a patch of disputed land

his group has claimed under Brazil's constitutional right to reparations

for descendants of runaway slaves. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington

Post)

The dry grass crackled under Almir Vieira Pereira's shoes as he walked along the edges of the roça,

a small patch of land he's been fighting to plant on for years. He

grabbed a handful of soil and watched it puff into a smoky cloud as it

settled back to the ground.

Brazil's northeastern backlands are known for their dryness. Perennial droughts have sent generations of northeasterners fleeing from impoverished farming towns like this one for the industrial cities of the South -- São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte. Barra do Parateca's soil had yet to recover from last year's lack of rain.

But dry or not, the ability to walk freely across this field marked a major victory for Pereira. He and a group of slave descendants from the roughly 1,500-person hamlet of Barra do Parateca have spent the last five years invading chunks of land across the area that they say are rightfully theirs under a well-known but haphazardly enforced article of the Brazilian Constitution. That law guarantees permanent, non-transferable land titles to Brazilians descended from the members of runaway slave settlements. Such communities of descendants are known in Brazil as "quilombos."

Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country and relatively underpopulated, but land ownership remains out of reach most of the nation's poor farmers, many of whose ancestors worked the fields for European overlords. The ability to plant one's own food marks the first step for people like Pereira in a long march out of poverty and toward independence.

"Our fight for land is all about producing food," Pereira, 39, said. "The great thinkers of the world, they're thinking about creating things, inventing things. We're still thinking about eating. If the government really wants racial reparations, they have to at least give us the possibility to think like equals."

Four years ago, anyone who looked across this 15-acre plot would have seen razed earth littered with broken ceramic tiles that had once served as the roof of a camp shelter. The cops had wiped out that settlement after the neighbors who owned the land, the Pereira Pinto family, failed to persuade Pereira and his fellow quilombo residents to vacate the premises.

Pereira and his group had had several run-ins with authorities before, but this time was different. Normally, they would be allowed to finish the harvest if they agreed to abandon the plot when they were done. This time, police destroyed the crops in front of a crowd of Barra residents.

"Everyone was crying and we couldn't do anything," Pereira's friend, Ducilene Magalhães, recalled. "We just watched."

These days, Pereira and Magalhães have arrived at an uneasy truce with the landowners. Though the owners are in the midst of pursuing legal action and have removed an irrigation system that once watered the field, they're also reluctantly allowing the quilombo members to harvest crops on a small patch of the property until the courts settle the dispute.

Although quilombos dotted the Brazilian landscape throughout the era of slavery, which lasted from the 1500s until 1889, they faded into history during the 20th century. Most of the legislators who approved the quilombo law, ratified in 1988 as part of the new Brazilian Constitution, viewed it as a symbolic gesture that would affect only a handful of families.

But in 2003, a decree by left-wing President Luiz Inácio "Lula" da Silva made it possible for virtually any black community to apply for quilombo status, if a majority of its residents so decided.

Since Lula's order, the number of certified quilombos has skyrocketed from fewer than three dozen to more than 2,400, with hundreds more in the process of applying for recognition. In total, more than 1 million Brazilians are demanding their constitutional right to land in what may become the largest slavery reparations program ever attempted.

In practice, however, the program remains a dead letter for many. Despite a constitutional guarantee and the lip service of almost 12 years of continuous Worker Party-led government, only 217 quilombos have received official land titles as of this year.

Impatient with the slow hand of Brazilian bureacracy, quilombos across the country like Barra do Parateca are invading the promised parcels of land, sometimes igniting violent conflicts with their wealthier neighbors in the process.

Brazil's northeastern backlands are known for their dryness. Perennial droughts have sent generations of northeasterners fleeing from impoverished farming towns like this one for the industrial cities of the South -- São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte. Barra do Parateca's soil had yet to recover from last year's lack of rain.

But dry or not, the ability to walk freely across this field marked a major victory for Pereira. He and a group of slave descendants from the roughly 1,500-person hamlet of Barra do Parateca have spent the last five years invading chunks of land across the area that they say are rightfully theirs under a well-known but haphazardly enforced article of the Brazilian Constitution. That law guarantees permanent, non-transferable land titles to Brazilians descended from the members of runaway slave settlements. Such communities of descendants are known in Brazil as "quilombos."

Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country and relatively underpopulated, but land ownership remains out of reach most of the nation's poor farmers, many of whose ancestors worked the fields for European overlords. The ability to plant one's own food marks the first step for people like Pereira in a long march out of poverty and toward independence.

"Our fight for land is all about producing food," Pereira, 39, said. "The great thinkers of the world, they're thinking about creating things, inventing things. We're still thinking about eating. If the government really wants racial reparations, they have to at least give us the possibility to think like equals."

Four years ago, anyone who looked across this 15-acre plot would have seen razed earth littered with broken ceramic tiles that had once served as the roof of a camp shelter. The cops had wiped out that settlement after the neighbors who owned the land, the Pereira Pinto family, failed to persuade Pereira and his fellow quilombo residents to vacate the premises.

Pereira and his group had had several run-ins with authorities before, but this time was different. Normally, they would be allowed to finish the harvest if they agreed to abandon the plot when they were done. This time, police destroyed the crops in front of a crowd of Barra residents.

"Everyone was crying and we couldn't do anything," Pereira's friend, Ducilene Magalhães, recalled. "We just watched."

These days, Pereira and Magalhães have arrived at an uneasy truce with the landowners. Though the owners are in the midst of pursuing legal action and have removed an irrigation system that once watered the field, they're also reluctantly allowing the quilombo members to harvest crops on a small patch of the property until the courts settle the dispute.

Although quilombos dotted the Brazilian landscape throughout the era of slavery, which lasted from the 1500s until 1889, they faded into history during the 20th century. Most of the legislators who approved the quilombo law, ratified in 1988 as part of the new Brazilian Constitution, viewed it as a symbolic gesture that would affect only a handful of families.

But in 2003, a decree by left-wing President Luiz Inácio "Lula" da Silva made it possible for virtually any black community to apply for quilombo status, if a majority of its residents so decided.

Since Lula's order, the number of certified quilombos has skyrocketed from fewer than three dozen to more than 2,400, with hundreds more in the process of applying for recognition. In total, more than 1 million Brazilians are demanding their constitutional right to land in what may become the largest slavery reparations program ever attempted.

In practice, however, the program remains a dead letter for many. Despite a constitutional guarantee and the lip service of almost 12 years of continuous Worker Party-led government, only 217 quilombos have received official land titles as of this year.

Impatient with the slow hand of Brazilian bureacracy, quilombos across the country like Barra do Parateca are invading the promised parcels of land, sometimes igniting violent conflicts with their wealthier neighbors in the process.

This

photo, taken July 5, 2010, shows the ruins of the quilombo

association's makeshift shelter, which the police destroyed weeks

before. (Roque Planas/The Huffington Post)

Few

who walk the lone paved street of the town of Barra do Parateca would

imagine that Brazil boasts the world's seventh-largest economy.

Lying off the banks of the São Francisco river, about 400 miles into the rain-starved interior of the state of Bahia, Barra do Parateca is reachable only by boat or by a bumpy ride along a dirt road. Braying donkeys wander freely, feeding on discarded cartons, plastic soda bottles and spoiled food that lies in piles on the ground because the town lacks regular trash collection.

The garbage embarrasses Pereira. An evangelical pastor, he's thrown himself into building Barra do Parateca's quilombo with the civic-minded, can-do attitude of a budding politician. (He did, in fact, run for local office recently and lost to a white man, which he said was a bitter experience for an Afro-Brazilian running in a majority-black district.) He wears pressed pants and button-down shirts, drinks soda instead of beer and wants future generations of Barra do Parateca's students to speak grammatically correct Portuguese, rather than the local dialects that often disregard subject-verb agreement.

But building a better Barra is a job that would try the patience of even the most progressive-minded idealist. While the boost in social spending during Brazil's past decade has helped alleviate the worst of the poverty, few people in town own land or any other productive enterprise that could lift Barra do Parateca into prosperity. Those who do have no intention of handing it over to people like Pereira.

Facing a life of toiling in someone else's field for a pittance or waiting to cash government social assistance checks, many residents instead choose to leave. In search of work, they head to cities like São Paulo, a metropolis of 20 million located 850 miles to the south.

Most of them wind up in "favelas," the violence-plagued slums that ring Brazil's cities. Others migrate to the interior of São Paulo state to pick oranges or cut sugar cane. In a town of roughly 1,500 residents, some 30 of Barra do Parateca's men left to work in São Paulo last year, all of them fathers, Pereira says. Another 15 told him of plans to leave this year.

Despite the hardship, Pereira doesn't want to leave the place where he was born. He wants Barra do Parateca to break out of its rut. And he sees land ownership, and the independence that comes with it, as the key.

By "land," he's quick to clarify, he means real land -- not the tiny patch that his neighbors begrudgingly let his quilombo use now. With land, Pereira says, he and his fellow quilombolas could produce their own food, with a little left over for sale in local markets.

"We don't want to keep depending on the government," Pereira said. "In Brazil, without land, you're no one."

Lying off the banks of the São Francisco river, about 400 miles into the rain-starved interior of the state of Bahia, Barra do Parateca is reachable only by boat or by a bumpy ride along a dirt road. Braying donkeys wander freely, feeding on discarded cartons, plastic soda bottles and spoiled food that lies in piles on the ground because the town lacks regular trash collection.

The garbage embarrasses Pereira. An evangelical pastor, he's thrown himself into building Barra do Parateca's quilombo with the civic-minded, can-do attitude of a budding politician. (He did, in fact, run for local office recently and lost to a white man, which he said was a bitter experience for an Afro-Brazilian running in a majority-black district.) He wears pressed pants and button-down shirts, drinks soda instead of beer and wants future generations of Barra do Parateca's students to speak grammatically correct Portuguese, rather than the local dialects that often disregard subject-verb agreement.

But building a better Barra is a job that would try the patience of even the most progressive-minded idealist. While the boost in social spending during Brazil's past decade has helped alleviate the worst of the poverty, few people in town own land or any other productive enterprise that could lift Barra do Parateca into prosperity. Those who do have no intention of handing it over to people like Pereira.

Facing a life of toiling in someone else's field for a pittance or waiting to cash government social assistance checks, many residents instead choose to leave. In search of work, they head to cities like São Paulo, a metropolis of 20 million located 850 miles to the south.

Most of them wind up in "favelas," the violence-plagued slums that ring Brazil's cities. Others migrate to the interior of São Paulo state to pick oranges or cut sugar cane. In a town of roughly 1,500 residents, some 30 of Barra do Parateca's men left to work in São Paulo last year, all of them fathers, Pereira says. Another 15 told him of plans to leave this year.

Despite the hardship, Pereira doesn't want to leave the place where he was born. He wants Barra do Parateca to break out of its rut. And he sees land ownership, and the independence that comes with it, as the key.

By "land," he's quick to clarify, he means real land -- not the tiny patch that his neighbors begrudgingly let his quilombo use now. With land, Pereira says, he and his fellow quilombolas could produce their own food, with a little left over for sale in local markets.

"We don't want to keep depending on the government," Pereira said. "In Brazil, without land, you're no one."

A

donkey feeds on garbage tossed along the roads of Barra do Parateca,

which lacks regular trash collection. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington

Post)

Brazil is among the world's most violent countries, with a homicide rate of 25 per 100,000 residents as of 2012.

A government report released last year suggested the persistent killings stem from a "culture of violence" fed by murderous conflicts between the drug cartels and other criminal gangs that have thrived in the cities' favelas. In the northern city of Maceió, the homicide rate in 2011 stood at a whopping 111 per 100,000, according to the report.

But Brazil's overflowing favelas are a symptom of larger problems that originate in places like Barra do Parateca, where waves of impoverished farmers, many if not most of them descended from slaves, have fled the countryside over the past half century. In 1950, the Brazilian census placed the urban population at 31 percent. As of 2013, that figure has climbed to 85 percent.

Land is the one major factor that pushes Brazilians to leave the countryside and crowd into the packed cities. Like in Barra do Parateca, land is all but unobtainable with the wages most Brazilian farm workers make.

"The highly unequal distribution of land in Brazil is clearly an important reason that Brazil's cities have grown in such a rapid, unequal and violent way," Sean Mitchell, an anthropology professor at Rutgers University who studies quilombos, wrote in an email to HuffPost. While Mitchell thinks it would be "impossible to roll back the haphazard and violent growth of Brazil's cities through reforms in the countryside," he added that "land reform would significantly alleviate violence in the countryside."

Land seemed an impossible dream for Pereira until 2005, when he helped found a local organization dedicated to addressing racial inequality. While working with the group, he learned about the Brazilian Constitution's quilombo clause: that communities descended from runaway slaves were entitled to own the land they lived on. All he had to do to gain access to the land was form an official association, collect signatures from a majority of the town's residents and take them to the country's capital, Brasília, to apply.

Pereira searched Barra do Parateca's history for evidence of its origins as a quilombo. Very little has been written about the tiny town, but he managed to find an account by a priest, published in 1991, that described the area's origins as a "fazenda," or ranch, owned by a Portuguese family during the colonial period. According to the document, the family raised sugar cane and herded cattle using slave labor.

"Those were my ancestors," Pereira said. "It was from that moment that we began to identify, we began to understand our origins."

He gathered signatures from more than half the town's residents and took the day-long bus ride to Brasilia to drop off the paperwork. The town became a certified quilombo in January 2006, and along with its status came a new school and health clinic.

But quilombo certification only extends to the town itself. The coveted farmlands that surround Barra do Parateca remain the private property of assorted ranchers and farmers.

And eight years after certification, the government has yet to publish the legally required technical study documenting Barra do Parateca's land claim, let alone negotiate indemnization with all the current landowners or transfer a title to Pereira and his community.

Representatives from the Institute of Colonization and Land Reform, or INCRA, which carries out the titling process, say they're overburdened by the massive number of claims, which as of this year have reached 569 in the state of Bahia alone, according to federal government figures.

Although the constitution guarantees quilombos' property rights, INCRA can't simply take chunks of land and hand them to new owners. Instead, it must compensate the titleholders, who generally resist the agency's attempts to take over their property, leading to lengthy legal disputes.

"We can't expropriate land -- we also have to indemnify," Itamar Rangel at the INCRA's office in Salvador da Bahia told HuffPost. "Brazilian law defends the property rights of any citizen."

That lack of efficiency isn't unique to the state of Bahia. INCRA estimates the total amount of land currently claimed by quilombos in Brazil to be around 4.4 million acres -- an area roughly the size of New Jersey.

But the government has issued just 217 land titles as of this year, having granted only three last year and three in 2012. At this rate, the growing backlog that now stands at roughly 2,200 quilombos won't be getting cleared any time soon.

In 2007, frustrated with the pace of Brazilian bureaucracy, Barra do Parateca's quilombo association stopped waiting and started planting. They planted along the river banks. They planted on land just outside the town. They rode boats up the river and walked into the forest to plant in isolated fields, setting up campsites along the way. Today, when the quilombo residents are able to harvest those crops, it helps supplement their modestly stocked pantries and refrigerators.

The landowners usually fight back. As often as not, landowners find the clandestine fields and let cattle loose to feed on the crops before they're harvested.

About a dozen landowners from Barra do Parateca are battling the quilombo association's claims. Of all those fights, none is more tense than the one involving the Pinto family.

A government report released last year suggested the persistent killings stem from a "culture of violence" fed by murderous conflicts between the drug cartels and other criminal gangs that have thrived in the cities' favelas. In the northern city of Maceió, the homicide rate in 2011 stood at a whopping 111 per 100,000, according to the report.

But Brazil's overflowing favelas are a symptom of larger problems that originate in places like Barra do Parateca, where waves of impoverished farmers, many if not most of them descended from slaves, have fled the countryside over the past half century. In 1950, the Brazilian census placed the urban population at 31 percent. As of 2013, that figure has climbed to 85 percent.

Land is the one major factor that pushes Brazilians to leave the countryside and crowd into the packed cities. Like in Barra do Parateca, land is all but unobtainable with the wages most Brazilian farm workers make.

"The highly unequal distribution of land in Brazil is clearly an important reason that Brazil's cities have grown in such a rapid, unequal and violent way," Sean Mitchell, an anthropology professor at Rutgers University who studies quilombos, wrote in an email to HuffPost. While Mitchell thinks it would be "impossible to roll back the haphazard and violent growth of Brazil's cities through reforms in the countryside," he added that "land reform would significantly alleviate violence in the countryside."

Land seemed an impossible dream for Pereira until 2005, when he helped found a local organization dedicated to addressing racial inequality. While working with the group, he learned about the Brazilian Constitution's quilombo clause: that communities descended from runaway slaves were entitled to own the land they lived on. All he had to do to gain access to the land was form an official association, collect signatures from a majority of the town's residents and take them to the country's capital, Brasília, to apply.

Pereira searched Barra do Parateca's history for evidence of its origins as a quilombo. Very little has been written about the tiny town, but he managed to find an account by a priest, published in 1991, that described the area's origins as a "fazenda," or ranch, owned by a Portuguese family during the colonial period. According to the document, the family raised sugar cane and herded cattle using slave labor.

"Those were my ancestors," Pereira said. "It was from that moment that we began to identify, we began to understand our origins."

He gathered signatures from more than half the town's residents and took the day-long bus ride to Brasilia to drop off the paperwork. The town became a certified quilombo in January 2006, and along with its status came a new school and health clinic.

But quilombo certification only extends to the town itself. The coveted farmlands that surround Barra do Parateca remain the private property of assorted ranchers and farmers.

And eight years after certification, the government has yet to publish the legally required technical study documenting Barra do Parateca's land claim, let alone negotiate indemnization with all the current landowners or transfer a title to Pereira and his community.

Representatives from the Institute of Colonization and Land Reform, or INCRA, which carries out the titling process, say they're overburdened by the massive number of claims, which as of this year have reached 569 in the state of Bahia alone, according to federal government figures.

Although the constitution guarantees quilombos' property rights, INCRA can't simply take chunks of land and hand them to new owners. Instead, it must compensate the titleholders, who generally resist the agency's attempts to take over their property, leading to lengthy legal disputes.

"We can't expropriate land -- we also have to indemnify," Itamar Rangel at the INCRA's office in Salvador da Bahia told HuffPost. "Brazilian law defends the property rights of any citizen."

That lack of efficiency isn't unique to the state of Bahia. INCRA estimates the total amount of land currently claimed by quilombos in Brazil to be around 4.4 million acres -- an area roughly the size of New Jersey.

But the government has issued just 217 land titles as of this year, having granted only three last year and three in 2012. At this rate, the growing backlog that now stands at roughly 2,200 quilombos won't be getting cleared any time soon.

In 2007, frustrated with the pace of Brazilian bureaucracy, Barra do Parateca's quilombo association stopped waiting and started planting. They planted along the river banks. They planted on land just outside the town. They rode boats up the river and walked into the forest to plant in isolated fields, setting up campsites along the way. Today, when the quilombo residents are able to harvest those crops, it helps supplement their modestly stocked pantries and refrigerators.

The landowners usually fight back. As often as not, landowners find the clandestine fields and let cattle loose to feed on the crops before they're harvested.