The 38th edition of the State of Black America®– One Nation Underemployed: Jobs Rebuild America – underscores a reality the National Urban League knows all too well – that the major impediments to equity, empowerment and mobility are jobs, access to a living wage and wealth parity. Amidst the discourse and debate about income inequality and other economic news-of-the-day, One Nation Underemployed: Jobs Rebuild America underscores the urgency of the jobs crisis—both un-and-under-employment.

Short of an anticapitalist revolution, how do African Americans and other communities of color recover from the losses of the Great Recession and forge a path to economic stability and upward mobility? The Urban League offers great data about our crises, but comes back- for the 38th time -with a plea to and plan to work with the very same corporate and governmental forces that have created our oppressive and exploitative conditions.

SOBA2014-SinglePgs

------------------------------------

March 2014- http://www.bls.gov

Investment in higher education by race and ethnicity

Recent research studies

cover the varying perspectives on education by ethnicity and race and

the methods in which families exert influence over educational choices.

In addition, a number of studies that are rooted in Human Capital Theory

evaluate returns to schooling—education increases an individual’s

productivity and contributes to an individual’s capacity to improve his

or her financial and social well-being. Using Consumer Expenditure

Survey microdata, this article extends previous research on human

capital and investment in education by examining the patterns of

educational expenditures by race and ethnicity. The results reveal that

differences in investment arise principally from (1) differences in

college attendance and (2) the likelihood to assume educational

expenditures. Once families decide to invest in their children’s higher

education, little difference exists in the level of expenditures between

racial and ethnic groups.

“Western parents try to respect their children’s individuality, encouraging them to pursue their true passions, supporting their choices, and providing positive reinforcement and a nurturing environment. By contrast, the Chinese believe that the best way to protect their children is by preparing them for the future, letting them see what they’re capable of, and arming them with skills, work habits, and inner confidence that no one can ever take away.”

As

an example shown by the excerpt from Chua’s book, recent popular

literature discusses the varying perspectives on education by ethnicity

and race and the ways in which families exert influence over educational

choices.2

Higher education, after all, contributes to an individual’s capacity to

earn a livelihood and improve his or her financial and social

well-being, regardless of race or ethnicity.

In his book Human Capital, Nobel laureate economist Gary Becker3 articulated the premise that human capital arises out of any activity that increases individual productivity.4

Education is one such activity that increases the productivity of the

individual, requiring the direct cost of the education (tuition, books,

and housing) and the foregone earnings during education. In much the

same way that a unit of physical capital such as production machinery

generates a stream of production benefits (lightbulbs, automobiles, or

basketballs) with market value, human capital that increases as a result

of an investment in education will generate an augmented stream of

earnings and social benefits that will accrue as long as the educational

investment has market and social values.

Human

capital is primarily produced in the family and in schools. According to

Becker, parents’ altruistic investment in the child’s education depends

on their willingness to forgo their own consumption for the sake of the

child and on the likelihood that the investment will yield economic and

intrinsic personal and social benefits for the child.

In

addition, because education improves human capital, society accrues the

benefits of a more productive workforce that contributes through

specialization and innovation. Moreover, families accrue the direct and

indirect benefits of family members who are more productive and better

able to provide greater economic support to the family. Families that

invest in the human capital of their children receive the social

benefits of higher education, to include increased social opportunities

and the positive social impression made by the individual and the

family. The family is integral to the investment decision as well as the

subsequent benefits to the child, the family, and society. In the words

of Becker,5

“No discussion of human capital can omit the influence of families on the knowledge, skills, health, values, and habits of their children. Parents affect educational attainment, marital stability, propensities to smoke and to get to work on time, and many other dimensions of their children’s lives.”

At an individual

and family level, various factors influence the level of education

investment. These factors include the family socioeconomic status (such

as the amount of disposable family income and the education level of the

parents), the ability of the child to complete his or her education,

and the perceived economic and social benefits. The weight given to

investing in education is therefore related to not only the stream of

economic benefits but also the underlying characteristics of the family

that chooses to invest.

Drawing on evidence from

the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE)

microdata, a household survey that provides information on the buying

habits of American consumers, this study extends previous research on

human capital and investment in education by examining differences in

educational expenditure patterns between race and ethnicity. We

disaggregate the investment decision into two separate stages and

explore any differences at each stage. First is the decision to attend

college. Second is the level of expenditures for education. An

individual who decides to attend college may incur different costs,

depending on the choice of an educational institution and family

background. Studying the amount an individual spends, given his or her

decision to attend college, may provide further insights into

differences in the educational investment decision.

In this article, parent’s education level refers to the education level of the reference parent. With the release of 2012 CE data, education of reference person was replaced by highest education level of any member in the consumer unit.

This newly defined education classification, although not used in the

analysis herein, does not change any statistical significance of the

results presented in this article.

Consequently,

this article evaluates whether race and ethnicity contribute to

differences in investments in higher education. An investment decision

includes both the decision to attend college and the amount of money

invested given that decision. Many studies stop at examining differences

in the likelihood to attend college by race and ethnicity, yet many

differences in investment may be uncovered in the level of expenditures

decided on for higher education. In this article, we first review the

discussion of returns to schooling and the decision to attend college.

Next, we describe the dataset we use for analyses. Finally, we discuss

in depth the pieces that make up the differences in an investment

decision by examining the decision to attend college by race and

ethnicity and then focusing on levels of expenditures differences for

higher education.

Returns to schooling and the decision to attend college: a literature review

Returns to schooling.

The essence of human capital theory is that investments in human

capital—schooling and training—raise a person’s income by increasing the

individual’s productivity and in satisfying society’s demand for more

highly remunerated skills. In the case of schooling, individuals forgo

money they would have earned during their working years and instead

incur direct educational costs to invest in their own human capital. The

individual’s rate of return is based on the investment value of the

gain in lifetime earnings.6

Other

research focuses on the wide variety of forms returns to education can

take, such as financial returns in the form of pay, nonmonetary

opportunities such as more job and schooling options, and nonmarket

returns; for example, the ability of the educated to use skills to

perform services for themselves such as tax preparation that would

otherwise be purchased.7

Although all of these benefits and those to society are important, the

focus of human capital returns to schooling revolves around the lifetime

earnings returns that come from additional education. A rich collection

of studies provides estimates of returns to education dating from the

late 1950s.8

These studies conclude that private rates of return vary by region,

income grouping, and gender. In addition, rates of return are highest in

primary education and diminish with additional years of education. In

the United States, the overall (primary through higher education)

private rate of return to investment in education is “on the order of 10

percent.”9

Other studies have considered race, ethnic, and gender differences in returns to schooling, in particular, higher education.10

The findings from many of these studies indicate that positive returns

to education are common across races, ethnicities, and the two genders.

Moreover, when differences in ability are considered, “little evidence

of differences in the return to school across racial and ethnic groups”

exists.11

Again, these studies, which employ different datasets at different

times, estimate annual gains from education ranging from 6 percent to 15

percent.

Taken together, a human capital

framework and the ensuing research lead to the following conclusions

about the value of schooling:

·

Additional years of schooling positively correlate with increased

earnings. This relationship holds for primary, secondary, and higher

education.

·

The decision to invest in education is one that yields a wide range of

benefits, including a positive rate of return for the individual and

society.

· The private annual rate of return varies but generally ranges from 8 percent to 10 percent.

Decision to attend college.

The likelihood of the decision to attend college hinges on the costs of

and the perceived returns (whether financial or personal) to schooling,

as just discussed. This decision is shown to influence conditions of

the family significantly, such as income, wealth, and education level.

Differences in college attendance by race and ethnicity have been well

studied, but results vary.

Studies have shown

that college attendance varies significantly by race and ethnicity.

Without controlling for family background,12

studies have consistently found that Hispanic and African American

families have lower levels of education and college attendance, while

Asians tend to have higher levels of education and college attendance.13

The focus of many other studies has been on estimating the effect of

family background factors in explaining differences in college

attendance. These studies indicate a wide range of results in explaining

college attendance gaps due to socioeconomic differences and academic

achievement. Some studies show that socioeconomic differences explain

all or at least a portion of the gap in college attendance. Other

studies have also expanded the analysis and discussed differences in

attendance between 2-year and 4-year colleges.

At

one end of the spectrum, several studies indicated that—given similar

academic achievement levels of the student and similar family

backgrounds—young African Americans were more likely to attend college.

Thomas Kane showed that at each Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT,

formerly Scholastic Aptitude Test) level, African American student

enrollment rates were higher than their White counterparts.14

Pamela Bennett and Yu Xie showed that African American students,

compared with their White counterparts, are more likely to attend

college, especially at low levels of family socioeconomic status.15

Audrey Light and Wayne Strayer showed that minorities are more likely

than their White counterparts to attend colleges of all quality levels.16

Laura Walter Perna found that African Americans are about 11 percent

more likely than Whites to enroll in a 4-year college or university in

the fall after graduating from high school.17

Many

studies indicate that college attendance differences are insignificant

after accounting for family background factors. Kane and Spizman showed

that lower average educational attainment of African Americans is the

result of differences in parental income, education, and geographical

location.18

Charles, Roscigno, and Torres showed that background inequalities

explain the entire African American–White gap in the likelihood of

college attendance.19

Sandra Black and Amir Sufi found that since the 1990s, at every point

of the socioeconomic status, African Americans were no more likely to

attend college than Whites.20 Two other studies have found that Hispanic high school graduates are as likely as Whites to attend college.21

Even

at lower levels of significance, studies generally show that

socioeconomic factors account for at least some of the difference in

college attendance among races. Min Zhan and Michael Sherraden showed

that when household assets are considered, a substantial portion of the

African American–White gap in college attendance disappears.22

Regarding

attendance at 2-year and 4-year institutions, Kao and Thompson found

that although African American and Hispanic students are more likely to

attend college than ever before, they are more likely than Whites or

Asians to attend a 2-year college than a 4-year institution.23

Cameron and Heckman found that Hispanics show the highest 2-year entry

rate compared with African Americans and Whites, which is partially

attributable to the regional concentration of Hispanics in states, such

as California and Texas, with extensive low-tuition community college

networks.24

Consumer expenditure survey dataset

The

analyses in this article are based on microdata from the Interview

Survey of the CE of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Data from

the years 2008, 2009, and 2010 contain 90,872 observations taken from

consumers who were interviewed between January 2008 and March 2011.25

Selected subsets of the complete dataset are used for various parts of

our analyses. (See appendix A for number of observations for each

subset.) CE interviews the sample family units on the basis of a

rotating panel, surveying about 7,000 consumer units26

each quarter. Each consumer unit is interviewed once per quarter for up

to five consecutive quarters. The Interview Survey is designed to

capture expenditure data that respondents can reasonably recall for a

period of 3 months or longer. In general, data captured include

relatively large expenditures.27

This

article examines the variation across consumer units, henceforth,

“households,” at each interview, to explain differences in educational

investment among racial groups and thus the article treats each

household as a unique observation.28

All summary statistics, parameter estimates, and variances in this

article are generated using weights created through balanced repeated

replication, a procedure necessary to compute unbiased variance

estimates through the CE’s use of a stratified random sample of

geographic areas around the United States.29

The data represent the U.S. population in all analyses performed in

this article. Results are derived with a SAS macro that the BLS

developed.

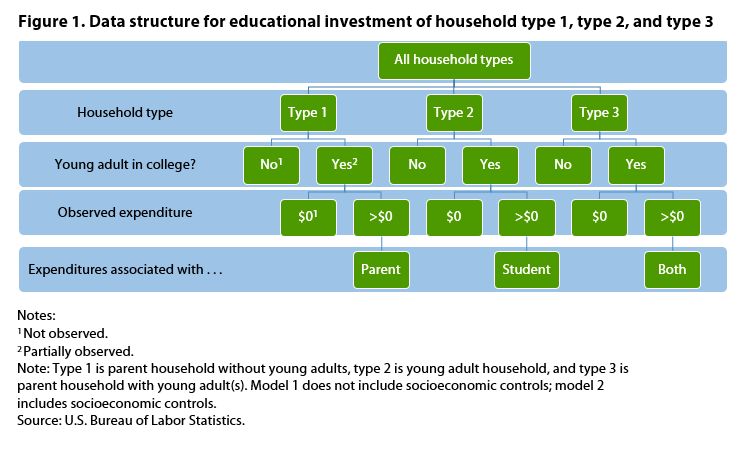

To disaggregate educational

expenditures, we provide a structure that outlines the decision to incur

expenditures and describes how the CE data are organized in accordance

with this structure. (See figure 1.) First, a qualified

16–24-year-old—one who graduated from high school but does not have a

bachelor’s degree, henceforth, a “young adult,”—decides whether to go to

college. Furthermore, if he or she decides to attend college, the

educational expenditure may be made by the parent(s), young adult, both,

or neither. For completeness, we discuss three types of households

relevant to educational expenditures:

· Type 1—parent household without young adults residing in the household

· Type 2—young adult household

· Type 3—parent household with young adult(s) residing in the household

Households

are identified as type 1 (78,686 observations) if no young adult member

is acknowledged, during the interview, to reside in that household.

Type 1 households include families (1) that do not have any young adult

members (regardless of residence) and (2) those who have one (or more)

young adult member(s) but who may be away (for college or living

separately), although we cannot distinguish between these two subtypes

in the data. Households identified as type 2 (4,099 observations)

comprise young adult members who are the head of their household. This

type includes those who are living apart30

from parents such as a college student. Type 3 (8,087 observations)

households are identified as those with at least one young adult member

who is not the head of a separate household and has at least one other

older member (e.g., parent).

For type 1

households, we do not observe whether a young adult is away at college;

we only know that, when we observe a positive expenditure for an

unobserved individual who is away from home, an individual (likely to be

a young adult) is away at college.31 For type 2 households, we observe the young adult’s college attendance decision32

and his or her own out-of-pocket expenditure for higher education. We

do not, however, observe the young adult’s family background. For type 3

households, we observe both the young adult’s college attendance

decision and the household expenditure for higher education.

Race and ethnicity.

An individual’s race is identified as White, African American, Asian,

or “other.” “Other” includes Native American, Pacific Islander, and

multiracial. Ethnicity is classified as Hispanic and non-Hispanic. For

the purpose of this article and because of limitations of sample size,

Hispanic origin will be considered as a subset of only the White racial

group. African American Hispanics and Asian Hispanics are grouped into

“other.” Thus, the racial and ethnic groups used for this article are

White (White non-Hispanics), Hispanics (White Hispanics), African

Americans (African American non-Hispanics), Asians (Asian

non-Hispanics), and other.33

Data control variables.

To control for variations in the data that may inadvertently bias model

results, we include indicators for year of interview, month of

interview, month of expenditure, part-time student, and female.

Socioeconomic variables.

For type 1 and type 3 households, factors associated with family

background are observed, including education of the parent(s) and total

outlays34 of the household, which is used as a proxy for permanent income.35 (See appendix B for more details.)

Other variables and model selection.

Additional variables such as occupation and assets were available to be

used in various parts of the analyses; however, the selection of

covariates to use in each model was based on a combination of intuition

and empiricism. Variables that had an economic relation and linearly

related to the dependent variable were added to each model. Selection

criteria36 were then applied and resulted in the final models that follows.

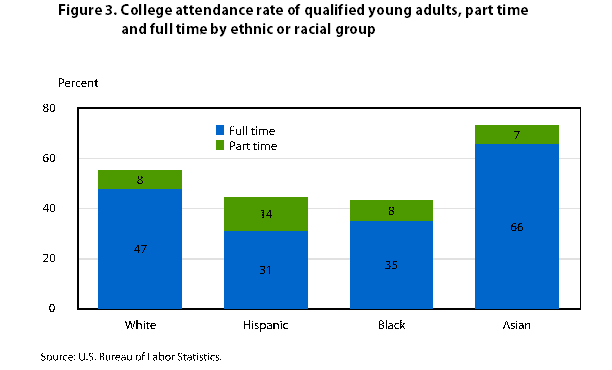

College attendance rates

Prior

to deciding on an amount to spend for higher education, individuals and

families must first decide whether a member of the family is to attend

college. As just discussed, the decision to attend is influenced by many

factors, such as family income, race, their parents’ education, and

wealth.

In our dataset, more than half of qualified young adults37

were in college, of which 83 percent were enrolled full time. Our data

show that Hispanics (45 percent) and African Americans (43 percent)

generally have lower college attendance rates than Whites (55 percent)

or Asians (73 percent). As with previous studies, family background,

such as their parents’ education and income, was significantly

associated with the likelihood of attending college. As parent’s

education level and income increase, the likelihood of a young adult

attending college significantly increases. The extent to which

socioeconomic differences explain differences in college attendance

among racial and ethnic groups varies among models, but socioeconomic

differences were generally found to account for some of the observed

differences.38

(See appendix C, table C-1.) Part-time college attendance rates for

Whites, African Americans, and Asians were between 7 percent and 8

percent, while Hispanics had a 14 percent part-time attendance rate.

(See figures 2 and 3.)

Tuition expenditure patterns for attendees

At the aggregate level, as with published CE tables,39

Hispanic and African American households have a lower average household

expenditure than White households do, whereas Asian households have a

higher average household expenditure. (See table 1.) However, these

overall averages are misleading, because they do not distinguish those

students who are attending college from those who are not.

| Race or ethnicity | Mean | Standard error |

|---|---|---|

| White | 409.2 | 27.4 |

| Hispanic | 177.3 | 49.2 |

| African American | 125.3 | 18.5 |

| Asian | 644.3 | 112.1 |

Note: “Other” group is omitted.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||

Once

an individual has decided to attend college, he or she must decide on

the amount to invest in higher education. In this section, we first

discuss the characteristics of households with college-attending

students. We then model the level of out-of-pocket tuition expenditures40

for those with a positive expenditure. Finally, we examine factors that

are associated with a zero or unobserved out-of-pocket tuition

expenditures.41

Profile of households with college-attending students.

Among households with college-attending students, family

characteristics vary significantly among racial and ethnic groups. Table

2 shows the characteristics of type 3 households—those with one or more

parents and one or more students—by race and ethnicity in the dataset

used for the analyses.

Education.

Compared with Hispanic and African American parents, White and Asian

parents of college-attending students have higher levels of education.

Whereas 33 percent of White parents and 30 percent of Asian parents

obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher, 18 percent of African American

parents and 10 percent of Hispanic parents obtained the same degree. At

the lower end of the education scale, 5 percent of White parents and 8

percent of Asian parents did not receive a high school diploma. In

contrast, 12 percent of African American and 32 percent of Hispanic

parents did not receive a high school diploma.

| Education of parents | White | Hispanic | African American | Asian |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than high school (percent) | 5 | 32 | 12 | 8 |

| High school (percent) | 27 | 24 | 27 | 32 |

| Some college, associate’s degree (percent) | 36 | 34 | 42 | 30 |

| Bachelor’s degree (percent) | 23 | 7 | 13 | 17 |

| Graduate degree (percent) | 10 | 3 | 5 | 13 |

| Annual income (annualized total outlays) (dollars)(1) | 67,269 | 48,327 | 48,868 | 58,667 |

| Have any tuition expenditures (percent) | 28 | 18 | 14 | 28 |

| Average quarterly tuition (dollars) | 2,806 | 1,356 | 1,606 | 3,397 |

| Female student (percent) | 58 | 62 | 58 | 47 |

| Notes: (1) Consumer unit type 3 households only (parents with young adults). Note: The term “total outlays” is a proxy for permanent income; we obtained annualized outlays by multiplying quarterly outlays by 4. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||

Income. Asian parents of college-attending students reported 13 percent less permanent income42

($58,700) than White parents ($67,300). Relative to the income of White

parents, Hispanic and African American parents had 28 percent and 27

percent less annual income, or $48,300 and $48,900, respectively.

Positive tuition expenditure.

Asian households were as likely as White households to have a positive

expenditure for education. However, Hispanics households were more than

one-third less likely than White households to have a positive

expenditure, while African Americans were only about half as likely.

Average tuition expenditure.

Of the households with positive tuition expenditures, Asians reported

21 percent higher expenditures than Whites. Hispanics and African

Americans reported 52 percent and 43 percent, respectively, lower

expenditures than Whites reported.

While

Hispanics and African Americans households with a student in college

had, on average, a lower probability of having a positive expenditure

and a lower amount of expenditure, they also had lower education and

lower total outlays. To ascertain whether certain racial or ethnic

groups tended to spend less (or more) on education because of their

average socioeconomic differences, we performed a regression analysis.

Observed out-of-pocket tuition expenditures.

We constructed a model for out-of-pocket positive tuition expenditures

and used the method of ordinary least squares to estimate not only the

relationship between race and ethnicity, but also socioeconomic

characteristics, and the level of positive tuition expenditures. (See

box that follows.)

A model for tuition expenditures

Because expenditures are truncated at zero, are clustered around lower values, and have a long tail (are right-skewed), a transformation of the dependent variable is applied to approximate normality. For each model, an optimal Box-Cox transformation is applied to distribute tuition expenditures more normally and to stabilize variance.1We start with an ordinary least squares model of (transformed) positive expenditures regressed on race and ethnicity, with data controls in which

where Yλ is a vector of (transformed) observed tuition expenditure for higher education; X is a matrix of indicators for race and ethnicity; β is a vector of corresponding parameter estimates; Z is a matrix of data controls, including indicators for interview year, interview month, tuition expenditure month, female, and part-time student; γ is a vector of corresponding parameter estimates; and ε is a vector of errors.

We then add socioeconomic factors to equation (1), yielding

where W is a vector of family background characteristics, including parent’s education level and annual permanent income,2 and η is a vector of corresponding parameter estimates.

Notes:

1 The optimal λ for consumer unit types 1, 2, and 3 are 0.12, 0.24, and 0.08, respectively.

2 The logarithm of income (annualized outlays) is used to overcome nonlinearity between permanent income and tuition expenditures.

The

regression model results indicate significant differences in tuition

expenditures by income, education, and race and ethnicity.

Income.

Family income has a significant effect on educational expenditures.

Ceteris paribus, for every $10,000 increase in annual permanent income,

average annual tuition expenditures increase between $200 and $400 for

type 1 households (parents without young adults) and between $120 and

$360 for type 3 households (parents with young adults).43 (See appendix C, table C-2.)

Education.

At household education levels of bachelor’s degree and below,

differences in tuition expenditures are insignificant. On average,

households with parents having a graduate degree had college tuition

expenditures 40 percent to 80 percent higher than households with

parents not having a graduate degree.44

Race and ethnicity.

Differences in the level of expenditure for tuition are most pronounced

for student-only households (type 2). Hispanic students, on average,

spent half the amount that an average White student spent on tuition. On

the other hand, Asians spent nearly twice as much as their White

counterpart. However, the extent to which family characteristics explain

the differences in expenditures remains uncertain for type 2

(student-only) households because these characteristics are unobserved

in the data. Also, because of the small sample size of African American

type 2 households, expenditure differences between this group and Whites

are not statistically significant.

For

parent-only (type 1) households, no significant differences in

expenditures were found between racial and ethnic groups. For student

and parent joint (type 3) households, Hispanics had 38 percent lower

tuition expenditures than Whites. However, when controlling for the

socioeconomic differences between Hispanics and Whites, we found that

Hispanics’ lower expenditures were not statistically significant.45

This finding indicates that permanent income and education level

effects accounted for nearly all the observed differences in tuition

expenditures between Hispanics and Whites. (See table 3 and appendix C,

table C-3.)

| Variable | Type 1 (model 1) | Type 1 (model 2) | Type 2 (model 1) | Type 3 (model 1) | Type 3 (model 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race or ethnicity | |||||

Hispanic

| –0.088 | –0.091 | –0.902 | –0.066 | –0.037 |

| (0.089) | (0.069) | (0.354)(1) | (0.020)(2) | (0.022)(3) | |

African American

| 0.002 | 0.055 | –0.640 | –0.036 | –0.020 |

| (0.076) | (0.064) | (0.528) | (0.024) | (0.025) | |

Asian

| 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.952 | 0.043 | 0.056 |

| (0.057) | (0.062) | (0.407)(1) | (0.028) | (0.033) | |

| Data controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Socioeconomic controls | No | Yes(4) | No(5) | No | Yes |

| Notes: (1) Significant at the 5-percent α level. (2) Significant at the 1-percent α level. (3) Significant at the 10-percent α level. (4) In-college part time and female not available. See appendix C, table C-3. (5) Socioeconomic controls not available. Note: Standard errors are in parenthesis. Type 1 is parent household without (visible) young adults, type 2 is young adult household, and type 3 is parent household with young adult(s). Model 1 does not include socioeconomic controls; model 2 includes socioeconomic controls. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||||

Unobserved and zero out-of-pocket expenditures.

The previous section addressed positive tuition expenditure

differences, yet another important aspect to address is the likelihood

of having a positive (and unobserved) expenditure.46A

household with a young adult attending college may not have an observed

positive expenditure for tuition. Many factors may prevent an

expenditure from being observed. Examples include scholarships or some

other financial aid covering all tuition fees,47

someone outside of the household covering the expenditure (especially

for type 2 households), or someone covering a tuition expenditure in a

month outside of the interview coverage months. Although the reasons for

zero out-of-pocket expenditures are unknown in the data, we examine

factors that are associated with the likelihood of having a positive

tuition expenditure for types 2 and 3, the households in which a young

adult in college is present. This last piece of modeling zero

out-of-pocket expenditures is necessary and important to complete the

analysis of investment in higher education. The box that follows

describes our model for zero out-of-pocket tuition expenditures.

A model for zero expenditures

The response variable, regardless of whether a tuition expenditure is positive or zero, is a binary response. We use a logit1 model with data controls for type 2 and type 3 households aswhere T indicates positive tuition expenditure; X is a matrix of indicators for race and ethnicity; β is a vector of corresponding parameter estimates; Z is a matrix of data controls, including indicators for interview year, interview month, female, and part-time student; and γ is a vector of corresponding parameter estimates. The response in a logistic regression is modeled as log-odds, that is, the log of the ratio of the probability of a positive expenditure versus a zero expenditure.

For type 3 households, we then included socioeconomic controls as

where in this equation, X, β, Z, and γ are as in equation (1); W is a matrix of family background characteristics, including parent’s education level and logarithm of total quarterly outlays, which are used as a proxy for permanent income; and η is a vector of corresponding parameter estimates.

Note:

1 We also used probit and linear probability models. The results were similar.

As

with the results for the levels of expenditures, results obtained from

models of zero expenditure indicate that income, education, and race and

ethnicity are important determinates of whether a household will have

positive expenditures.

Income.

Not surprisingly, permanent income is significantly associated with the

likelihood of having any tuition expenditure. The probability of having

out-of-pocket tuition expenditure increases with family income level.

This relationship is expected because families with lower permanent

income tend to receive more financial aid,48

increasing the likelihood of complete tuition coverage. Compared with

families with an annual permanent income of $20,000 or less, families

with $120,000 or more with a college-going child are about 6.5 times

more likely to have tuition expenditure. (See figure 4.) Even after

controlling for other covariates, such as race, other socioeconomic

factors, and data controls, the income effect remains highly

significant. (See appendix C, table C-2.)

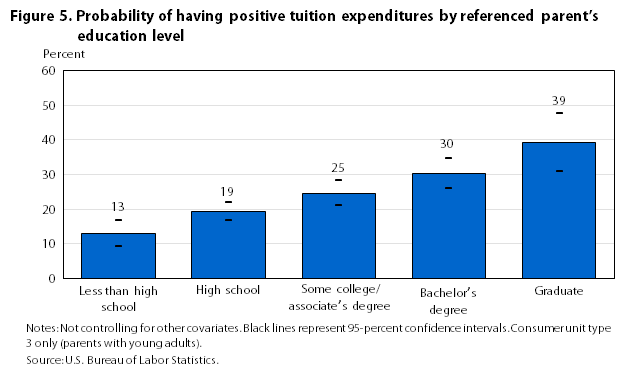

Education.

As expected, as parents’ education level increases, the probability of

having positive tuition expenditure increases. (See figure 5.) Even when

other factors such as permanent income are controlled, the probability

still increases with education level.49 (See appendix C, table C-2, for results obtained from the model.)

Race and ethnicity.

Even when differences in family background are controlled, our model

yields results which indicate that, of those households with one or more

members who attend college, African American households are

significantly less likely to have an observed positive expenditure for

tuition compared with White households. Asian households show a

marginally significantly higher probability of having a positive

expenditure.50 (See table 4 and appendix C, table C-2.)

| Variable | Type 2 (model 3): without socioeconomic controls | Type 3 (model3): without socioeconomic controls | Type 3 (model 4): with socioeconomic controls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race or ethnicity | |||

Hispanic

| 0.134 | –0.194 | –0.029 |

| (0.203) | (0.160) | (0.151) | |

African American

| –1.154 | –0.560 | –0.476 |

| (0.309)(1) | (0.176)(2) | (0.163)(2) | |

Asian

| 0.648 | 0.279 | 0.233 |

| (0.336)(3) | (0.141)(4) | (0.124)(3) | |

| Data controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Socioeconomic controls | No(5) | No | Yes |

| Notes: (1) Significant at the 0.1-percent α level. (2) Significant at the 1-percent α level. (3) Significant at the 10-percent α level. (4) Significant at the 5-percent α level. (5) Socioeconomic controls not available. Note: Standard errors are in parenthesis. Type 2 is young adult household, and type 3 is parent household with young adult(s). Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | |||

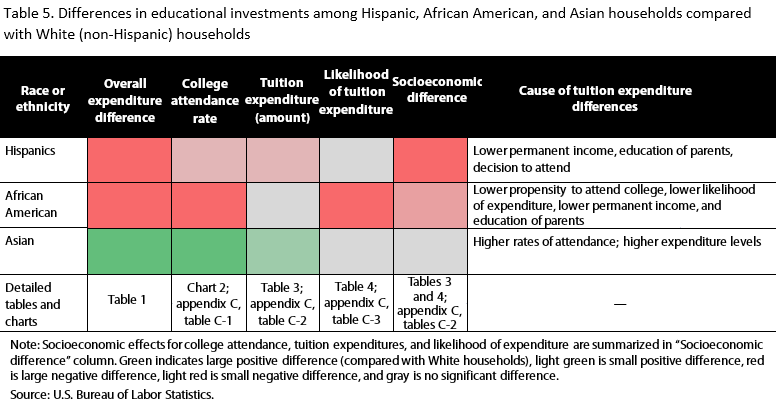

DIFFERENCES

IN INVESTMENT IN HIGHER EDUCATION between racial and ethnic groups

arise from differences in college attendance, the level of expenditures

for higher education and, to a greater extent, the likelihood of having

positive education expenditures. Some of the differences, as shown in

table 5, can be attributed to differences in family socioeconomic

status, such as parent’s education level and permanent income. In

narrative terms, our results are as follows:

·

Relative to White households, Hispanic households tend to have lower

rates of college attendance and some evidence shows lower levels of

tuition expenditures, as well. Our results indicate that the overall

lower levels of household tuition expenditures for Hispanics are due

primarily to generally lower levels of permanent income, parent’s

education level, the decision to attend college and, to some extent, the

levels of tuition expenditure of students. However, after accounting

for differences in education and permanent income, Hispanic households

do not differ significantly either in the likelihood of having any

tuition expenditures or in the level of expenditures.

·

African American young adults tend to have lower rates of college

attendance and, among those who decide to attend college, a lower

probability of having any tuition expenditure, even when family

permanent income and education level are considered. However, of those

who have any tuition expenses, the levels of expenditures are not

significantly different from those of White families. The primary

contributing factors to lower levels of household tuition expenditure by

African Americans are socioeconomic differences, a lower likelihood to

attend college, and the higher likelihood of having no expenditures even

when one decides to attend college.

·

Asian young adults have higher rates of college attendance than any

other race or ethnicity. Asian parents do not have a significantly

higher level of tuition expenditures. However, some evidence points to

higher levels of expenditures from students in student-only households.

These results suggest that Asian households’ overall higher expenditures

for education are primarily due to the higher rates of college

attendance in Asian families, and, to some extent, the higher levels of

tuition expenditures by Asian student-only households.

With

a variety of factors contributing to the overall decision of college

investment, differences arise among racial and ethnic groups.

Notwithstanding the complexity of socioeconomic factors, our findings

suggest that differences in permanent income and education level of

parents are important in the decision to attend college, in the level of

expenditures, and in the likelihood of having a positive expenditure

for education. Controlling for these important factors, we find that

whereas the decision whether to invest may be different for Asians,

African Americans, and Hispanics, the amount of investment, for the most

part, is not significantly different from that of Whites.

Previous

studies have shown that similar returns to schooling exist across

different races and ethnicities, even if the likelihood to attend

college is different. However, given the decision to invest and given

evidence of positive expenditures, we found no significant differences

in the level of investment. These results suggest that, although the

perceived returns to schooling may be different for different races and

ethnicities, the investment value of education for those who choose to

invest is unambiguous, both in perception and in effect. Returning to

the earlier discussion of higher education and human capital, we

conclude that once a decision to invest in higher education is made and

positive expenditures are registered by a family, little difference

exists in the amount for education investments between the racial and

ethnic groups studied. In other words, we find that all racial and

ethnic groups believe in and invest in the human capital idea that

investments in higher education are economically beneficial to their

children.

Acknowledgments

The authors

would like to thank BLS Senior Economist Geoffrey Paulin from the Office

of Prices and Living Conditions for his invaluable comments, review,

guidance, and patience through many revisions of this article; BLS

Branch Chief and Supervisory Economist Steve Henderson, BLS Supervisory

Economist Bill Passero, and BLS Economists Adam Reichenberger and

Lucilla Tan, all also from the Office of Prices and Living Conditions;

BLS Supervisory Economist Martin Kohli from the New York Regional Office

for Economic Analysis and Information, BLS Deputy Associate

Commissioner Michael Strople from the Office of Field Operations, BLS

Supervisory Economist Amar Mann from the San Francisco Regional Office,

BLS Associate Commissioner Jay Mousa from the Office of Field

Operations, and Research Economist Harley Frazis from the Office of

Employment and Unemployment Statistics, for their review and comments;

and Regina Wu, formerly an intern at BLS, for her research assistance,

comments, and review.

Appendix A: Number of observations

| Race or ethnicity | All observations by type | In college by type | Observed positive tuition expenditure by type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| White | 55,301 | 2,956 | 4,539 | 2,070 | 2,192 | 868 | 476 | 644 |

| Hispanic | 8,951 | 404 | 1,707 | 165 | 783 | 41 | 28 | 130 |

| African American | 9,126 | 454 | 1,130 | 205 | 485 | 47 | 13 | 66 |

| Asian | 3,608 | 169 | 461 | 144 | 314 | 57 | 41 | 88 |

| Other | 1,700 | 116 | 250 | 71 | 118 | 12 | 10 | 29 |

| Total | 78,686 | 4,099 | 8,087 | 2,655 | 3,892 | 1,025 | 568 | 957 |

| Note:

Type 1 is parent household without young adults, type 2 is young adult

household, and type 3 is parent household with young adult(s). Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||

Appendix B: Variables

| Variable | Values and range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer unit type | 1: No qualified 16–24-year-old in consumer unit | Consumer unit type |

| 2: Qualified 16–24-year-old without parent(s) in consumer unit | ||

| 3: Qualified 16–24-year-old with parent(s) in consumer unit | ||

| In college | 1: In college full time | For qualified 16–24-year-olds only |

| 2: In college part time | ||

| 3: Not in college | ||

| Tuition expenditure for higher education | [$0, ∞) ϵ ℝ | Quarterly expenditure |

| Tuition indicator | 1: Tuition > 0 | — |

| 0: Tuition = 0 or blank | ||

| Tuition expenditure month | [1, 13] ϵ ℕ | Month in which the expenditure was made; month 13 indicates same amount each month |

| Race and ethnicity | 1: White non-Hispanic | Race and ethnicity of head of household; other includes Native American, Pacific Islander, and multiracial |

| 2: White Hispanic | ||

| 3: African American non-Hispanic | ||

| 4: Asian non-Hispanic | ||

| 5: Other | ||

Female

| 0: Male | Gender of qualified 16–24-year-olds |

| 1: Female | ||

| Year | [2008, 2011] ϵ ℕ | Year of interview |

| Interview month | [1, 12] ϵ ℕ | Month in which the interview was conducted |

Education level

| 1: No high school graduate | For types 1 and 3 consumer unit head of households only |

| 2: High school graduate | ||

| 3: Some college, associate’s degree | ||

| 4: Bachelor’s degree | ||

| 5: Master’s, professional, or doctorate degree | ||

| Total outlays less tuition expenditures for higher education | [$0, ∞) ϵ ℝ | Quarterly outlays; for types 1 and 3 consumer unit head of households only; proxy for permanent income |

| Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||

Appendix C: Additional tables

| Variable | Type 3: without socioeconomic covariates | Type 3: with socioeconomic covariates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard error | Estimate | Standard error | |

| Intercept | 0.047 | (0.065) | –3.027 | (0.840)(1) |

| Hispanic | –.206 | (.131) | –.037 | (.138) |

| African American | –.315 | (.113)(2) | –.249 | (.114)(3) |

| Asian | .737 | (.149)(1) | .634 | (.157)(1) |

| Other | –.089 | (.246) | –.077 | (.267) |

Interview year

| ||||

2008

| –.228 | (.064)(1) | –.229 | (.066)(1) |

2009

| –.062 | (.052) | –.061 | (.055) |

2000

| .134 | (.044)(2) | .151 | (.046)(1) |

Interview month

| ||||

January

| –.015 | (.061) | –.027 | (.061) |

February

| –.059 | (.057) | –.051 | (.061) |

March

| –.056 | (.065) | –.061 | (.066) |

April

| –.034 | (.066) | –.032 | (.072) |

May

| .028 | (.082) | .040 | (.083) |

June

| .059 | (.074) | .060 | (.074) |

July

| –.122 | (.064)(4) | –.136 | (.067)(3) |

August

| .019 | (.061) | .042 | (.065) |

September

| .040 | (.078) | .005 | (.074) |

October

| .013 | (.066) | .014 | (.074) |

November

| .024 | (.068) | .042 | (.070) |

Education

| ||||

Less than high school

| — | — | –.538 | (.084)(1) |

High school

| — | — | –.279 | (.078)(1) |

Some college, associate’s degree

| — | — | .064 | (.066) |

Graduate degree

| — | — | .472 | (.142)(1) |

| Log income | — | — | .340 | (.091)(1) |

| Notes: (1) Significant at the 0.1-percent α level. (2) Significant at the 1-percent α level. (3) Significant at the 5-percent α level. (4) Significant at the 10-percent α level. Note: Type 3 is parent household with young adult(s). Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||

| Variable | Type 1 (model 1) | Type 1 (model 2) | Type 2 (model 1) | Type 3 (model 1) | Type 3 (model 2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard error | Estimate | Standard error | Estimate | Standard error | Estimate | Standard error | Estimate | Standard error | |

| Intercept | 2.239 | (0.105)(1) | 0.383 | (0.293) | 5.543 | (0.718)(1) | 1.777 | (0.051)(1) | 1.310 | (0.145)(1) |

| Hispanic | –.088 | (.089) | –.091 | (.069) | –.902 | (.354)(2) | –.066 | (.020)(3) | –.037 | (.022)(4) |

| African American | .002 | (.076) | .055 | (.064) | .640 | (.528) | –.036 | (.024) | –.020 | (.025) |

| Asian | .001 | (.057) | .007 | (.062) | .952 | (.407)(2) | .043 | (.028) | .056 | (.033) |

| Other | .045 | (.188) | .081 | (.142) | .717 | (.510) | –.095 | (.042)(2) | –.073 | (.041)(4) |

Interview year

| ||||||||||

2009

| .035 | (.059) | .041 | (.059) | –.326 | (.349) | –.020 | (.028) | –.010 | (.023) |

2010

| .033 | (.061) | .015 | (.064) | –.114 | (.382) | –.016 | (.033) | –.003 | (.029) |

2011

| .026 | (.059) | .020 | (.056) | –.230 | (.505) | –.007 | (.027) | .006 | (.022) |

Interview month

| ||||||||||

January

| .054 | (.092) | .031 | (.086) | .368 | (.809) | –.020 | (.051) | –.015 | (.053) |

February

| .155 | (.089)(4) | .119 | (.078) | –.784 | (.621) | –.001 | (.039) | .002 | (.039) |

March

| .020 | (.082) | –.007 | (.075) | –.991 | (.659) | –.027 | (.039) | –.024 | (.038) |

April

| .019 | (.099) | .026 | (.086) | –.751 | (.638) | –.015 | (.038) | –.005 | (.037) |

May

| .041 | (.110) | .027 | (.104) | –.992 | (.651) | –.018 | (.049) | –.011 | (.050) |

June

| –.107 | (.092) | –.096 | (.085) | –.091 | (.580) | –.060 | (.040) | –.047 | (.038) |

July

| –.031 | (.095) | –.024 | (.090) | –.050 | (.608) | –.122 | (.055)(2) | –.125 | (.052)(2) |

August

| –.009 | (.096) | –.017 | (.086) | .082 | (.749) | –.048 | (.050) | –.044 | (.049) |

September

| .021 | (.069) | .025 | (.064) | –.186 | (.580) | –.051 | (.033) | –.047 | (.029) |

October

| .005 | (.077) | .016 | (.066) | .082 | (.522) | –.044 | (.035) | –.041 | (.033) |

November

| .020 | (.064) | .027 | (.058) | –.028 | (.547) | –.035 | (.030) | –.035 | (.027) |

Expenditure month

| ||||||||||

January

| .267 | (.050)(1) | .233 | (.049)(1) | 1.647 | (.375)(1) | .069 | (.025)(3) | .073 | (.023)(3) |

February

| .055 | (.065) | .034 | (.058) | .090 | (.586) | .034 | (.023) | .035 | (.021) |

March

| .205 | (.060)(3) | .200 | (.057)(3) | .490 | (.773) | .037 | (.030) | .030 | (.030) |

April

| .224 | (.066)(3) | .189 | (.061)(3) | .171 | (.444) | .057 | (.035) | .051 | (.035) |

May

| .113 | (.068) | .088 | (.062) | –.650 | (.573) | .041 | (.030) | .036 | (.029) |

June

| .084 | (.061) | .046 | (.052) | –.245 | (.310) | .099 | (.032)(3) | .104 | (.030)(3) |

July

| .279 | (.056)(1) | .257 | (.046)(1) | .369 | (.669) | .094 | (.042)(2) | .077 | (.040)(4) |

August

| .294 | (.048)(1) | .231 | (.044)(1) | 1.129 | (.601)(4) | .097 | (.026)(1) | .095 | (.027)(1) |

September

| .210 | (.051)(1) | .171 | (.043)(1) | .418 | (.402) | .073 | (.029)(2) | .074 | (.029)(2) |

October

| .141 | (.053)(2) | .133 | (.043)(3) | .282 | (.484) | .016 | (.032) | .023 | (.031) |

November

| –.017 | (.061) | –.025 | (.057) | .604 | (.588) | –.039 | (.041) | –.033 | (.040) |

December

| .273 | (.047)(1) | .265 | (.043)(1) | .481 | (.419) | .072 | (.015)(1) | .065 | (.014)(1) |

| In college part time | — | — | — | — | –.912 | (.282)(3) | –.080 | (.017)(1) | –.067 | (.019)(3) |

| Female | — | — | — | — | .028 | (.156) | –.014 | (.013) | –.011 | (.013) |

Education

| ||||||||||

Less than high school

| — | — | –.014 | (.070) | — | — | — | — | –.007 | (.032) |

High school

| — | — | –.024 | (.044) | — | — | — | — | –.003 | (.016) |

Some college, associate’s degree

| — | — | .095 | (.028)(3) | — | — | — | — | .062 | (.018)(3) |

Graduate degree

| — | — | .161 | (.046)(3) | — | — | — | — | .076 | (.022)(3) |

| Log income | — | — | .183 | (.028)(1) | — | — | — | — | .043 | (.016)(3) |

| Notes: (1) Significant at the 0.1-percent α level. (2) Significant at the 5-percent α level. (3) Significant at the 1-percent α level. (4) Significant at the 10-percent α level. Note: Type 1 is parent household without young adults, type 2 is young adult household, and type 3 is parent household with young adult(s). Model 1 does not include socioeconomic controls; model 2 includes socioeconomic controls. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||||||

| Variable | Type 2 (model 3) | Type 3 (model 3) | Type 3 (model 4) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard error | Estimate | Standard error | Estimate | Standard error | |

| Intercept | –1.906 | (0.254)(1) | –1.257 | (0.101)(1) | –8.325 | (0.971)(1) |

| Hispanic | .134 | (.203) | –.194 | (.160) | –.029 | (.151) |

| African American | –1.154 | (.309)(1) | –.560 | (.176)(2) | –.476 | (.163)(2) |

| Asian | .648 | (.336)(3) | .279 | (.141)(4) | .233 | (.124)(3) |

| Other | –.050 | (.453) | .082 | (.183) | .044 | (.195) |

| In college part time | –.042 | (.179) | –.474 | (.145)(2) | –.358 | (.153)(4) |

| Female | .033 | (.162) | –.094 | (.090) | –.066 | (.096) |

Interview year

| ||||||

2008

| .205 | (.131) | .072 | (.091) | .079 | (.092) |

2009

| .091 | (.095) | .158 | (.071)(4) | .181 | (.072)(4) |

2000

| –.023 | (.135) | –.117 | (.055)(4) | –.094 | (.057)(3) |

Interview month

| ||||||

January

| –.477 | (.317) | –.250 | (.156) | –.295(1) | (.156)(3) |

February

| .709 | (.221)(2) | .361 | (.145)(4) | .461 | (.155)(2) |

March

| .452 | (.151)(2) | .465 | (.120)(1) | .471 | (.126)(1) |

April

| .337 | (.209) | .287 | (.142)(4) | .293 | (.149)(4) |

May

| –1.011 | (.315)(2) | –.937 | (.147)(1) | –.912 | (.151)(1) |

June

| –.372 | (.394) | –.481 | (.161)(2) | –.505 | (.170)(2) |

July

| .268 | (.245) | –.183 | (.099)(3) | –.248 | (.104)(4) |

August

| –.479 | (.534) | –.599 | (.170)(1) | –.584 | (.166)(1) |

September

| .283 | (.146)(3) | .453 | (.129)(1) | .413 | (.134)(2) |

October

| .550 | (.190)(2) | .568 | (.123)(1) | .528 | (.130)(1) |

November

| .405 | (.154)(2) | .541 | (.138)(1) | .611 | (.138)(1) |

Education

| ||||||

Less than high school

| — | — | — | — | –.382 | (.176)(4) |

High School

| — | — | — | — | –.236 | (.096)(4) |

Some college, associate’s degree

| — | — | — | — | .031 | (.087) |

Graduate degree

| — | — | — | — | .469 | (.178)(2) |

| Log income | — | — | — | — | .745 | (.100)(1) |

| Notes: (1) Significant at the 0.1-percent α level. (2) Significant at the 1-percent α level. (3) Significant at the 10-percent α level. (4) Significant at the 5-percent α level. Note: Type 2 is young adult household and type 3 is parent household with young adult(s). Model 3 does not include socioeconomic controls; model 4 includes socioeconomic controls. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. | ||||||

Notes

1 New York: Penguin Press, 2011.

2 See also Sandra Tsing Loh, “My Chinese American problem—and ours,” The Atlantic Monthly, April 2011, p. 83–91.

3Gary S. Becker, Human Capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press, 1994).

4 Jacob Mincer’s book Schooling, experience, and earnings (New York: Columbia

University Press, 1974) is also credited with providing a theoretical

and empirical basis for evaluating human capital and earnings.

5Gary S. Becker, “Human capital,” in David R. Henderson, The concise encyclopedia of economics, Library of Economics and Liberty (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2008), http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/HumanCapital.html.

6Societies

invest in human capital in the form of educational facilities,

programs, and subsidies. The social rate of return is based on the

benefits to society of having a more highly educated workforce, less the

cost of providing the educational services required to achieve those

benefits. In evaluating the rate of return to schooling, human capital

theory factors in the effects of cognitive ability and technological

change on individual human capital and economic growth. Briefly, the

reasoning is that the cognitive ability of the individual contributes to

the returns to schooling because those with higher cognitive abilities

select schooling over paid work, and therefore, the observed returns

actually relate to the individual’s innate abilities rather than the

level of schooling. The difficulty in distinguishing the contribution of

ability from that of schooling has led some economists to conclude that

“education and cognitive ability are so strongly associated that the

wage effects of the two cannot be separated for all groups . . . . The

real problem is that ability and schooling appear to be inseparable—all

interaction and not main effects—even if ability is perfectly observed.”

See James Heckman and Edward Vytlacil, “Identifying the role of

cognitive ability in explaining the level of and change in the return to

schooling,” Working Paper 7820 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of

Economic Research, August 2000), p. 18. Other researchers have also

evaluated the effects of “signaling” ability on rates of return to

schooling. The idea is that, in the absence of another tangible measure

of ability, achievements in higher education allow employers to sort

prospective employees on the basis of the presumed “signal” that the

individual has enhanced productivity. A National Bureau of Economic

Research study concluded that although high school graduates returns to

ability are negligible, college graduation “plays more than just a

signaling role in the determination of wages. . . . Graduation from

colleges allows individuals to directly reveal their ability to

potential employers.” In other words, differences in ability do not lead

to significant wage differences for high school graduates without

experience but are more tangible among college graduates and are

reflected in differences in wages. Moreover, among college graduates, no

estimated differences exist in wages or returns to ability by race. For

more information, see Peter Arcidiacono, Patrick Bayer, and Aurel

Hizmo, “Beyond signaling and human capital: education and revelation of

ability,” Working Paper 13951 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of

Economic Research, April 2008).

7Burton A. Weisbrod, “Education and investment in human capital,” part 2, “Investment in human beings,” Journal of Political Economy, October 1962, pp. 106–123.

8 For

a useful survey of studies in various countries over nearly 50 years,

see George Psacharopoulos and Harry Anthony Patrinos, “Returns to

investment in education: a further update,” Education Economics 12, no. 2 (September 2002), pp. 111–134.

9 Ibid., p. 116.

10 Fred

Hines, Luther Tweeten, and Martin Redfern, “Social and private rates of

return to investment in schooling, by race-sex groups and regions,” Journal of Human Resources, Summer 1970, pp. 318–340; Susan Averett and Sharon Dalessandro, “Racial and gender differences in the returns to 2-year and 4-year degrees,” Education Economics, March 2001, pp. 281–292; Lisa Barrow and Cecilia Elena Rouse, “Do returns to schooling differ by race and ethnicity?” Working Paper 2005-02 (Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, February 2005), pp. 34; and Lisa Barrow and Cecilia Elena Rouse, “The economic value of education by race and ethnicity,” Economic Perspectives, 2Q/2006 (Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 2006), pp. 14–27.

11 Barrow and Rouse, “The economic value of education,” p. 23.

12

Family background, or socioeconomic factors, may be captured through a

variety of proxies, such as income, wealth, education, etc.

13 See Current Population Survey (CPS): Statistical abstract of the United States: 2012,

“Table 229. Educational attainment by race and Hispanic origin: 1970 to

2010” and “Table 230. Educational attainment by race, Hispanic origin,

and sex: 1970 to 2010” (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012), http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0229.pdf; and Economic news release: college enrollment and work activity of high school graduates new release (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 8, 2011), http://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/hsgec_04082011.htm.

14 Thomas J. Kane, “Race, college attendance, and college completion” (U.S. Department of Education, 1994), http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED374766.

15

Pamela R. Bennett and Yu Xie, “Revisiting racial differences in college

attendance: the role of historically Black colleges and universities,” American Sociological Review, August 2003, pp. 567–580.

16 Audrey Light and Wayne Strayer, “From Bakke to Hopwood: does race affect college attendance and completion?” Review of Economics and Statistics 84, February 2002, pp. 34–44.

17 Laura Walter Perna, “Differences in the decision to attend college among African Americans, Hispanics, and Whites,” The Journal of Higher Education special issue: “The shape of diversity” (March 2000), pp. 117–141.

18 Thomas J. Kane and Lawrence. M. Spizman, “Race, financial aid awards, and college attendance,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology, January 1994, pp. 85–96.

19 Camille Z. Charles, Vincent J. Roscigno, and Kimberly C. Torres, “Racial inequality and college attendance: the mediating role of parental investments,” Social Science Research 36, March 2007, pp. 329–352.

20 Sandra E. Black and Amir Sufi, “Who goes to college—differential enrollment by race and family background,” Working Paper No. 9310 (National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2002).

21 Philip T. Ganderton and Richard Santos, “Hispanic college attendance and completion: evidence from the high school and beyond surveys,” Economics of Education Review 14, March 1995, pp. 35–46; and Perna, “Differences in the decision to attend college.”

22 Min Zhan and Michael Sherraden, “Assets and liabilities, race/ethnicity, and children’s college education,” Children and Youth Services Review, November 2011, pp. 2168–2175.

23Grace

Kao and Jennifer S. Thompson, “Racial and ethnic stratification in

educational achievement and attainment,” Annual Review of Sociology,

August 2003, pp. 417–442.

24 Stephen V. Cameron and James J. Heckman, “The dynamics of educational attainment for Black, Hispanic, and White males,” Journal of Political Economy 109, June 2001, pp. 455–499.

25 Expenditures refer to October 2007 through December 2010.

26 A

consumer unit comprises (1) all members of a particular household who

are related by blood, marriage, adoption, or other legal arrangements;

(2) a person living alone or sharing a household with others or living

as a roomer in a private home or lodging house or in permanent living

quarters in a hotel or motel but who is financially independent; or (3)

two or more persons living together who use their income to make joint

expenditure decisions. The three major expense categories that determine financial independence are housing, food, and other living expenses. To be considered financially independent, the respondent has to provide, entirely or in part, at least two of the three major expense categories.

27 For more information on expenditures, see “Appendix A: description of the Consumer Expenditure Survey,” Consumer Expenditure Anthology, 2011, Report 1030 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, July 2011), pp. 47–48, http://www.bls.gov/cex/anthology11/csxanthol11.pdf.

28 A unique observation is also known as a “unique NEWID.” NEWID is a global identifier in CE, which identifies each observational unit.

29 For more details on balanced repeated replication, see David Swanson’s “Standard errors in the 2011 Consumer Expenditure Survey” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011), http://www.bls.gov/cex/ce_se_2011.pdf.

30 The word “apart” signifies that the young adult does not live in the same household as the parent(s).

31 Tuition expenditures of type

1 households for the individual not seen in the household are captured

through a gift code, indicating whether the expenditure was for someone

outside of the household and whether it was an expenditure for college.

We do not know, however, the age of the individual for whom the

expenditure was made.

32 Data are captured through the code designating “in college full or part-time or not in college code.”

33 “Other” includes Native American (Hispanic and non-Hispanic), Pacific Islander (Hispanic and non-Hispanic), multiracial (Hispanic

and non-Hispanic), African American Hispanic, and Asian Hispanic. For

African Americans and Asians, individuals of Hispanic origin consisted

of less than 2 percent of each population.

34 Total outlays less tuition expenditures for higher education were used throughout this article. (See appendix B in this article for details.)

35 According to the “permanent-income hypothesis,” expenditures are made on the basis of levels of wealth rather than current income. Thus, total outlays indicate a consumer’s tastes and preferences better than current income does. See Milton Friedman, A Theory of the Consumption Function (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957), p. 6.

36 Based on Akaike information criterion (AIC), similar results were found with Bayesian information criterion (BIC), also known as the Schwarz criterion.

37 Young adults were from type 2 and type 3 households, only.

38 Results are based on logit models of college attendance on race, data controls, and family socioeconomic factors for type

3 households. Asians were consistently found to have a significantly

higher likelihood of going to college, regardless of any socioeconomic

differences. For Hispanics and African Americans, socioeconomic factors

explained some but not all of the difference in their lower likelihood

of attending college. (See appendix C, table C-1.)

39 For more information, see

“Table 2100. Race of reference person: average annual expenditures and

characteristics, Consumer Expenditure Survey, 2008” (U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics), http://www.bls.gov/cex/2008/Standard/race.pdf;

Table 2100. Race of reference person: average annual expenditures and

characteristics, Consumer Expenditure Survey, 2009” (U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics, October 2010), http://www.bls.gov/cex/2009/Standard/race.pdf; and

“Table 2100. Race of reference person: average annual expenditures and

characteristics, Consumer Expenditure Survey, 2010” (U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics, September 2011), http://www.bls.gov/cex/2010/Standard/race.pdf.

40 Our analyses also considered other expenses for higher education, such as room and board, textbooks. However, we did not observe any significant differences by race and ethnicity. Thus, we focused our

study of expenditures on tuition only. The results using total

expenditures, including other expenses for college, were similar.

41 Because of the limitations of the data, we could not explicitly account for differences in the amount of financial aid received across race and ethnicity,

which may affect the levels and likelihood of an out-of-pocket tuition

expenditure. A study showed that, except for Asian students, White students receive the least amount of financial aid; see Susan Borowski, “Scholarships and the White male: disadvantaged or not?” Insight into Diversity, April to May 2012, pp. 14–17, http://unival.com/PDF/InsightIntoDiversityMagazine_April-May%20Issue.pdf.

42 Data are based on quarterly outlays multiplied by 4.

43 Estimates were evaluated at annual permanent income levels between $20,000 and $120,000 for the baseline group, i.e., White, male student, parent with a bachelor’s degree, with default data controls.

44 Data were estimated for White households with a male student and an average annual income of $70,000, with default data controls.

45 Expenditures were evaluated with default data controls, as usual.

46

Zero expenditures, or “inhibitions” to observing a positive

expenditure, are essentially the first hurdle to overcome in a variation

of a double-hurdle model. However, in this article, the discussion of

zero expenditures is deferred until after a discussion of the level of

expenditures (second-hurdle in the model). (See John G. Cragg, “Some

statistical models for limited dependent variables with application to

the demand for durable goods,” Econometrica, September 1971, pp. 829–844.

47 If

a scholarship or some other kind of financial aid directly pays the

student’s tuition or reduces the tuition paid, the observed

out-of-pocket expenditure will be reduced. However, if a scholarship or

other financial aid is transferred to one’s bank account, it shows as a

source of income and the out-of-pocket expenditure will not be reduced.

48 Aid is based on each price of college. See Mark Kantrowitz, “Expected family contribution (EFC) calculator,” FinAid! The SmartStudent™ guide to financial aid, http://www.finaid.org/calculators/finaidestimate.phtml.

49

Testing for differences in the probability of having a positive tuition

expenditure between education levels indicates that parents with a

graduate degree have a significantly higher probability than those with

less than a high school diploma.

50 Scholarships

specific to minorities, as well as the effects of affirmative action,

also may contribute to a lower probability of an out-of-pocket

expenditure for non-Whites. See Borowski, “Scholarships and the White male.”

No comments:

Post a Comment